Hopefully, you’ve been able to play around with Apple’s Swift Testing framework. It’s the modern way of writing tests in Swift and works with techniques like Swift Macros.

In this lesson, we’re going to write similar tests as in the previous lesson, but we’re making use of Swift Testing.

A look at the core differences

Before we dive into writing tests using Swift Testing, it’s important to have an overview of some important differences:

- We no longer use

XCTAPIs likeXCTestCaseorXCTAssert - Expectations are not supported in Swift Testing

- You’ll use structs over classes and macros like

@Test

This course focuses on Swift Concurrency, and I won’t cover all the details regarding Swift Testing. However, as you may know, I also run a blog called SwiftLee. You might not be surprised that I wrote about Swift Testing there! Therefore, I encourage you to read my articles regarding Swift Testing if you’re new to this framework.

Testing for an empty search query

Let’s start by rewriting the XCTest for an empty search query:

@MainActor

func testEmptyQuery() async {

let articleSearcher = ArticleSearcher()

await articleSearcher.search("")

XCTAssertEqual(articleSearcher.searchResults, ArticleSearcher.articleTitlesDatabase, "Should return all articles")

}

The Swift Testing variant looks pretty similar:

@Test

@MainActor

func testEmptyQuery() async {

let articleSearcher = ArticleSearcher()

await articleSearcher.search("")

#expect(articleSearcher.searchResults == ArticleSearcher.articleTitlesDatabase)

}

The main difference here is that we’re marking our method with @Test and we’re making use of the #expect method instead of XCTAssertEqual. Other than that, we can also mark the method with @MainActor and async—pretty straightforward!

Awaiting asynchronous callbacks

It becomes more interesting when we have to deal with sleeps like we do in the other testing method:

@MainActor

func testWithSearchQuery() async {

let articleSearcher = ArticleSearcher()

let expectation = self.expectation(description: "Search complete")

/// Use observation tracking to track changes to the @Observable searchResults property.

_ = withObservationTracking {

articleSearcher.searchResults

} onChange: {

expectation.fulfill()

}

/// Perform the actual search for Article Three.

articleSearcher.searchWithSearchTask("three")

/// Asynchronously await for the expectation to fulfill.

await fulfillment(of: [expectation], timeout: 10.0)

/// Assert the result.

XCTAssertEqual(articleSearcher.searchResults, ["Article three"], "Should return article three")

}

Swift Testing does not support expectations, so we need to devise an alternative technique to make this work. In our case, we’re not awaiting any results—the search happens in a new Task and runs asynchronously. Therefore, we need a way to await the change using observation tracking in Swift Testing as well.

We can do this by using withCheckedContinuation:

@Test

@MainActor

func testWithSearchQuerySearchTask() async {

let articleSearcher = ArticleSearcher()

await withCheckedContinuation { continuation in

_ = withObservationTracking {

articleSearcher.searchResults

} onChange: {

continuation.resume()

}

articleSearcher.searchWithSearchTask("three")

}

#expect(articleSearcher.searchResults == ["Article three"])

}

The test appears to be similar to our XCTest variant, but utilizes Swift Testing syntax.

Using a confirmation inside tests

When we would write a test for the search method which doesn’t utilize the search task property, it could look as follows:

@Test

@MainActor

func testWithSearchQuery() async {

let articleSearcher = ArticleSearcher()

await articleSearcher.search("three")

#expect(articleSearcher.searchResults == ["Article three"])

}

This is structured concurrency at its best—we evaluate all logic from top to bottom. However, this test does not validate whether observation tracking works as expected. For this to work, we can make use of the [confirmation(_:expectedCount:isolation:sourceLocation:_:)](https://developer.apple.com/documentation/testing/confirmation\(_:expectedcount:isolation:sourcelocation:_:\)-5mqz2) method. This would look as follows:

@Test

@MainActor

func testWithSearchQueryAndObservation() async {

let articleSearcher = ArticleSearcher()

/// Create and await for the confirmation.

await confirmation { confirmation in

/// Start observation tracking.

_ = withObservationTracking {

articleSearcher.searchResults

} onChange: {

/// Call the confirmation when search results changes.

confirmation()

}

/// Start and await searching.

/// Note: using `await` here is crucial to make confirmation work.

/// the confirmation method would otherwise return directly.

await articleSearcher.search("three")

}

#expect(articleSearcher.searchResults == ["Article three"])

}

As described with inline comments, the confirmation method only works if you await an asynchronous method at its end. It’s not like a regular continuation method that we used in the previous code example—it examines whether the confirmation callback is called by the time the configured closure scope ends. In other words, if we do not use await, the confirmation call is evaluated and results in a failure of confirmation. This is also the reason why we can’t use this solution with out currentSearchTask example.

How about using setUp and tearDown?

Well, this is more of a Swift Testing-related question! But I’m happy to answer it here as well. In Swift Testing, you make use of the init and deinit methods instead:

final class ArticleSearcherSwiftTesting {

init() async throws {

// Call any asynchronous logic.

}

deinit {

// Call any asynchronous logic.

}

// ...

}

Note that you can only use the deinit if you’re defining your test as a class. A class is not required; you’ll often use structures in Swift Testing.

You might have noticed that we can’t call asynchronous methods inside our deinit. For the sake of this example, I’ve added two dummy methods to our ArticleSearcher:

/// Dummy methods for our testing examples.

/// This allows us to demonstrate how to use setUp and tearDown methods in both XCTest and Swift Testing.

extension ArticleSearcher {

func prepareDatabase() async {

/// Imagine preparing the database here.

}

func closeDatabase() async {

/// Imagine closing the database here.

}

}

Calling the prepareDatabase() method is straightforward:

@MainActor

final class ArticleSearcherSwiftTesting {

let articleSearcher = ArticleSearcher()

init() async throws {

await articleSearcher.prepareDatabase()

}

deinit {

// Call any teardown logic.

}

// ...

}

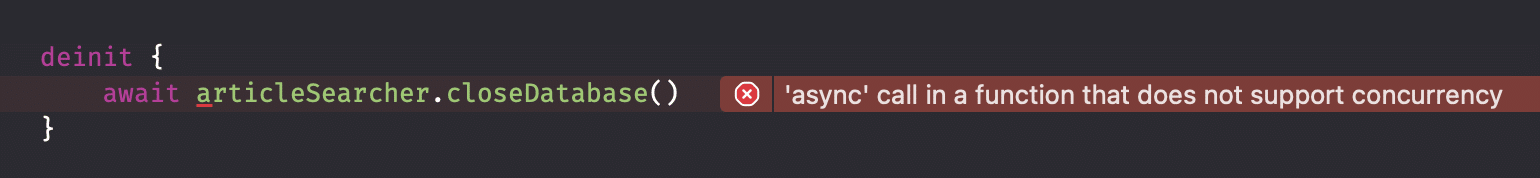

It becomes more challenging when we want to call asynchronous logic inside the deinit:

The deinit method does not support calling asynchronous methods by default.

In this case, we have two options:

- Using a

Task { }wrapper - Marking

deinitasisolated

The latter only works if our test is marked with an actor and our logic to call from the deinit matches that same actor isolation:

isolated deinit {

articleSearcher.closeDatabase()

}

It will, however, not allow calling any methods that are explicitly marked with async. Therefore, it’s not a solution for us to use in this example.

Instead, we could write the deinit as follows:

deinit {

Task {

await articleSearcher.closeDatabase()

}

}

This, however, results in the following error:

You need to understand that deinit is called when an object is moving out of memory. There’s no way to keep it in memory a little longer just because we need to do a clean up. In other words, we’re calling into self.articleSearcher which requires to retain self, which is not allowed.

We need to look into another solution called Test Scoping Traits.

Using Test Scoping Traits for asynchronous clean ups

Bear with me, this is going to be a new way of looking at tests. We will introduce so-called test traits, which will provide a specific test scope. This scope will be able to run code before and after each test, exactly what we need.

We start by defining a new Environment structure inside our test class:

@MainActor

final class ArticleSearcherSwiftTesting {

@MainActor

struct Environment {

@TaskLocal static var articleSearcher = ArticleSearcher()

}

// ...

}

I see this as the environment to use when writing tests. Instead of defining them in your class itself, we wrap them in an Environment structure for a clear access point. We make use of the @TaskLocal attribute to allow us to overwrite the value when needed.

Next, we’re going to define the trait itself:

struct ArticleSearcherDatabaseTrait: SuiteTrait, TestTrait, TestScoping {

@MainActor

func provideScope(for test: Test, testCase: Test.Case?, performing function: () async throws -> Void) async throws {

print("Running for test \(test.name)")

let articleSearcher = ArticleSearcher()

try await ArticleSearcherSwiftTesting.Environment.$articleSearcher.withValue(articleSearcher) {

await articleSearcher.prepareDatabase()

try await function()

await articleSearcher.closeDatabase()

}

}

}

We conform to three protocols:

SuiteTrait: to allow using the trait for a whole test suite.TestTrait: to allow using the trait for individual tests.TestScoping: the protocol required to return an actual scope. This is the protocol that allows us to define the singleprovideScopemethod that you see.

We have to mark the method with @MainActor as we’re dealing with ArticleSearcher, which still conforms to @MainActor. Inside the method, we’re using the withValue(...) method to overwrite the task local value. It binds the task-local to the specific value for the duration of the synchronous operation. In other words, we overwrite the value for a single test.

Inside the closure, we’re calling the prepareDatabase() before and the closeDatabase after the function() method. The function() method is what will call the original test. We can use this scope by configuring the test trait:

@Test(ArticleSearcherDatabaseTrait())

func testEmptyQuery() async {

await Environment.articleSearcher.search("")

#expect(Environment.articleSearcher.searchResults == ArticleSearcher.articleTitlesDatabase)

}

provideScopeto set up the task local valueprepareDatabase()to prepare the databasetestEmptyQuery()for running the actual testcloseDatabase()to clean up the database after the test is completed

It’s essential to access the articleSearcher via the Environment structure inside tests. Otherwise, we would not utilize the TaskLocal value, and we would access an unprepared database.

Similarily, we can make use of the trait inside a Suite to apply it to all tests:

@Suite(ArticleSearcherDatabaseTrait())

@MainActor

final class ArticleSearcherSwiftTesting {

// ...

}

Either way works, and it depends on what you need to figure out which one works best. Traits are Swift’s solution to setting up and tearing down before each individual test.

Summary

Swift Testing is the modern way of writing tests in Swift. It comes with first-class support for concurrency, but does require traits to perform teardown logic after each individual test.

In the next lesson, we’re going to dive into another approach of writing tests. We will look at an open-source framework called Swift Concurrency Extras.