While the Sendable protocol allows us to mark classes, structures, and enums as sendable, we can’t use it to mark functions and closures as sendable. For this, Swift introduced the @Sendable attribute.

Why you should use @Sendable

You use the @Sendable attribute to indicate that any values a function or closure captures must be sendable. It basically means that it’s likely that a captured value will be passed around isolation domains and should be thread-safe by being sendable.

Functions are also reference types and currently can’t conform to protocols. In Swift, functions come in various forms—global functions, nested functions, accessors (like getters, setters, and subscripts), and closures. Passing functions across concurrency domains can be valuable, enabling more functional programming patterns within Swift Concurrency.

How to use @Sendable

Imagine having the following contacts store:

actor ContactsStore {

private(set) var contacts: [Contact] = []

func add(_ contacts: [Contact]) {

self.contacts.append(contentsOf: contacts)

}

func removeAll(_ shouldBeRemoved: (Contact) -> Bool) async {

contacts.removeAll { contact in

return shouldBeRemoved(contact)

}

}

}

The actor synchronizes access, and we can only modify contacts from the same actor isolation domain. However, we want to introduce a new clean-up method that runs in the background. We could do this by introducing a nonisolated method that starts a new task with a background priority:

extension ContactsStore {

nonisolated func cleanUpContactsInTheBackground(_ shouldBeRemoved: @escaping (Contact) -> Bool) {

Task(priority: .background) {

await removeAll(shouldBeRemoved)

}

}

}

Note

You might be new to nonisolated and actors in general. Don’t worry too much about it now, we will go deeper into this in a future module.

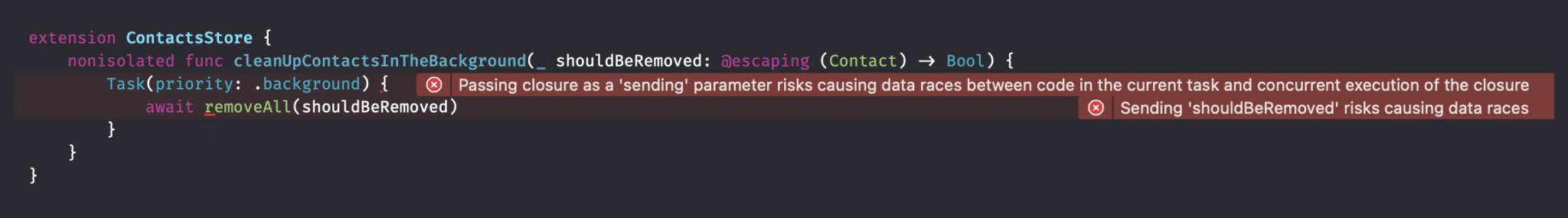

As soon as we’ve created the new method, we run into the following compiler errors:

Functions that are used across isolation domains require to be marked as @Sendable.

We passed the closure across isolation domains, meaning any captured values could risk data races. We could rewrite the method to use the closure directly instead of passing it forward:

nonisolated func cleanUpContactsInTheBackground(_ shouldBeRemoved: @escaping (Contact) -> Bool) {

Task(priority: .background) {

await removeAll { contact in

/// Note that we're now calling the closure here instead of passing it forward to the actor:

return shouldBeRemoved(contact)

}

}

}

However, this would still result in a compiler error:

This shows several compiler errors related to functions used across isolation domains. The latter is clear: we’re sending a function from a task-isolation domain to an actor-isolation domain. We’ve learned that we can only guarantee thread-safe access at compile-time if types are marked as sendable. This is where the @Sendable attribute comes into place:

/// Note that we've now added the `@Sendable` attribute:

nonisolated func cleanUpContactsInTheBackground(_ shouldBeRemoved: @escaping @Sendable (Contact) -> Bool) {

Task(priority: .background) {

await removeAll { contact in

return shouldBeRemoved(contact)

}

}

}

The @Sendable attribute makes functions conform to Sendable and will trigger compile-time checks for any captured values. In case there aren’t any non-sendable values, adding this attribute will be enough to make the compilation successful.

How functions are validated at compile time

To better understand the impact of the @Sendable attribute, it’s valuable to look at use-case examples.

In the following example, we’re using a static string which implicitly conforms to Sendable. This compiles successfully:

store.cleanUpContactsInTheBackground { contact in

contact.name.contains("van der")

}

If we change the code to capture a static string instead, the compiler is still happy:

let searchQuery = "van der"

store.cleanUpContactsInTheBackground { contact in

contact.name.contains(searchQuery)

}

The searchQuery property is immutable, so there’s no risk of data races. As soon as we change the searchQuery to a mutable variable:

var searchQuery = "van der"

store.cleanUpContactsInTheBackground { contact in

contact.name.contains(searchQuery)

}

We’ll run into the following error:

This is the result of a compile-time check due to the @Sendable attribute, and it shows how powerful these checks for thread-safe access are. This is an interesting case though: why can’t the compiler accept this capture using copy-on-write since a String is a value type?

Using a capture list to create an immutable snapshot

We can solve the above error by using a capture list:

var searchQuery = "van der"

store.cleanUpContactsInTheBackground { [searchQuery] contact in

contact.name.contains(searchQuery)

}

Swift forces an explicit capture list to clarify which values will be safely transferred into the concurrent function’s context. This is also known as capturing by-value—you capture the value that is current at that time.

Captures of immutable values introduced by let are implicitly by-value; any other capture must be specified via a capture list. When you explicitly capture a variable by-value, you ensure that the closure works with an immutable snapshot of the data at the moment the closure is created, avoiding accidental mutations from other threads before the value is actually used.

But we’re using a value type here, so aren’t we automatically copying the value at that time?

This is what I thought as well. You would expect Swift to be smart enough to capture van der at the moment we call into store.cleanUpContactsInTheBackground. I decided to validate this on the Swift Forums and will update this lesson as soon as I know more.

Summary

We can use the @Sendable attribute to mark functions as Sendable. The compiler will start checking for thread-safe access of captured variables, ensuring there’s no risk for data races when working with functions used across isolation domains.

In the next lesson, we’ll look into using @unchecked Sendable.