Now that we know how to mark types as sendable, it’s time to dive deeper. Sometimes, you’ll run into cases where you expect a compiler error while it doesn’t appear. This could be the result of region-based isolation.

What is region-based isolation?

Swift Concurrency organizes values into isolation domains based on actor and task boundaries. When code runs in separate isolation domains, it can execute at the same time. The Sendable system enforces safe concurrency by preventing non-Sendable values from being shared across these boundaries, ensuring there’s no simultaneous access to mutable states. However, this also introduces a strict limitation—blocking certain programming patterns that, while safe from data races, are no longer allowed.

This is where region-based isolation comes into place. It’s a way for the compiler to verify whether a non-sendable type is only used within the same scope, ruling out the possibility of data races.

For example, imagine having the following non-sendable class:

class Article {

var title: String

init(title: String) {

self.title = title

}

}

The class is non-final, has a mutable member, and doesn’t conform to Sendable. This would typically be a perfect recipe for strict concurrency compiler errors.

If we would use it inside our SendableChecker as follows:

struct SendableChecker: Sendable {

func check() {

let article = Article(title: "Swift Concurrency")

Task {

print(article.title)

}

}

}

We would pass it from a nonisolated context into a task-isolated context. While the article crosses isolation domains, a compiler error doesn’t show up. This is because region-based isolation applies—there’s no mutation happening within the same scope, so the compiler knows it’s thread-safe to pass the article around.

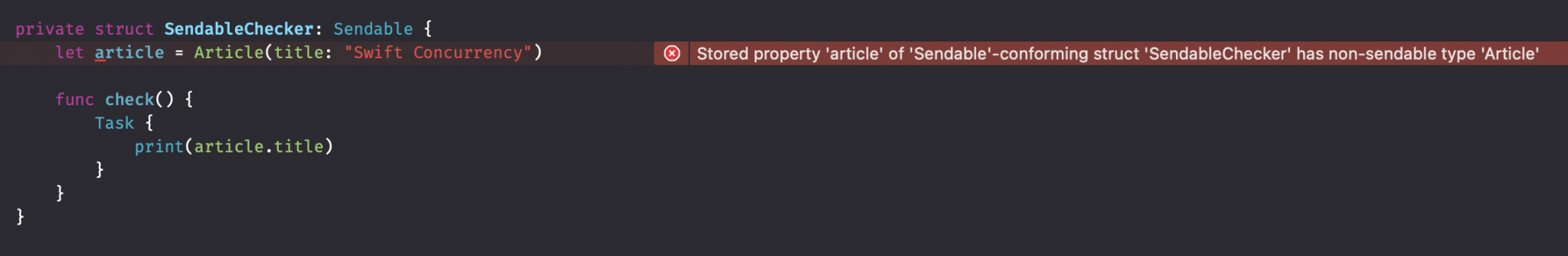

If we would define the article as a property instead:

A non-sendable type will be detected by the compiler if it’s not in a region-based isolation.

It’s no longer defined within the region of the check() method and a compiler error shows up.

Understanding control flow sensitive diagnostics

Sendable rules are loosened due to control flow-sensitive diagnostics determining whether a non-sendable value can safely be transferred between isolation domains. This is possible due to isolation regions that allow the compiler to reason conservatively if a value can result in data races. The compiler knows this If a value is not used after the point of transfer.

We can validate this by updating the earlier code example that compiled successfully:

struct SendableChecker: Sendable {

func check() {

let article = Article(title: "Swift Concurrency")

Task {

print(article.title)

}

print(article.title)

}

}

We added another print statement at the end of the check() function scope. This means we access the value after transferring it to the task’s isolation domain. Due to this, a data race could occur and the compiler has to show a compiler error:

With region-based isolation, Swift drastically reduces the number of times we’ll have to use Sendable.

Sending parameter and result values using the sending keyword

There are more cases where you can tell there’s no risk for data races, but the compiler still complains. For these scenarios, we could benefit from using the sending keyword. Using sending:

- Ensures that once a value is passed, it cannot be accessed from the original location.

- Prevents race conditions by enforcing ownership transfer.

- Allows for optimized performance by avoiding redundant copies.

Imagine having an actor that we use for printing out article titles:

actor ArticleTitleLogger {

func log(article: Article) {

print(article.title)

}

}

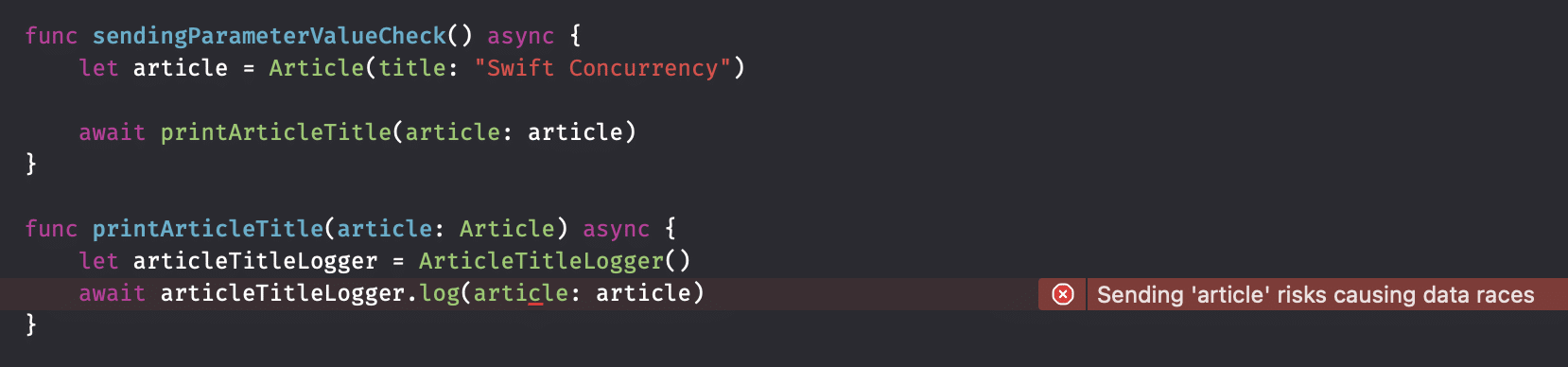

If we would use it as follows:

Passing a non-sendable Article to the actor causes a data race compiler error.

We would run into a compiler error due to a potential data race. However, the article value is defined in a local region, and isn’t mutated, so we know there’s no risk of a data race here. In this case, we can use the sending keyword to enforce ownership transfer to the printArticleTitle method:

func printArticleTitle(article: sending Article) async {

let articleTitleLogger = ArticleTitleLogger()

await articleTitleLogger.log(article: article)

}

By using the sending keyword, we enforce ownership transfer of the article value. We basically move the local-region checks toward the inner body of this method, and we ensure the value cannot be accessed from the original location anymore.

While the code would now compile:

func sendingParameterValueCheck() async {

let article = Article(title: "Swift Concurrency")

await printArticleTitle(article: article)

}

func printArticleTitle(article: sending Article) async {

let articleTitleLogger = ArticleTitleLogger()

await articleTitleLogger.log(article: article)

}

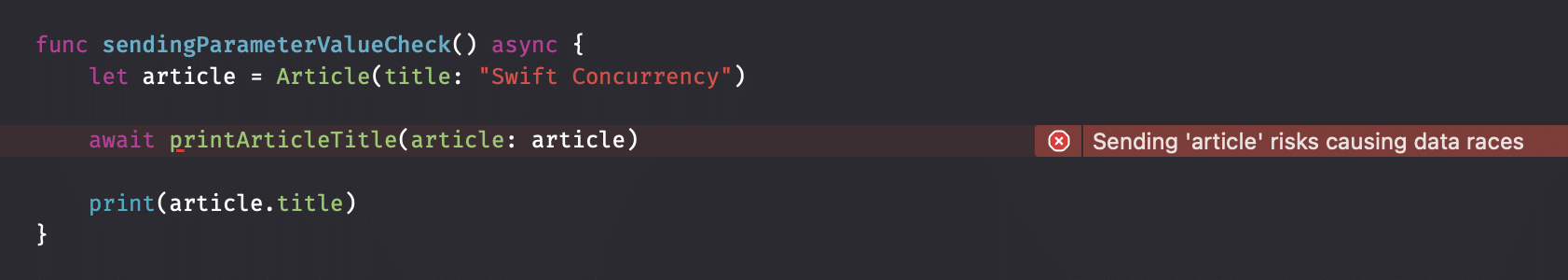

It would not anymore if we added a print statement after sending the value:

After sending the article value, we can no longer access it anymore since it’s not sendable and would risk data races.

Due to region-based isolation diagnostics, the compiler knows the value has been sent into the printArticleTitle method and cannot be accessed outside of that new disconnected context.

Sending result values

A similar pattern can occur when working with result values. Imagine having a method to create a new Article instance:

@SomeGlobalActor

func createArticle(title: String) -> Article {

return Article(title: title)

}

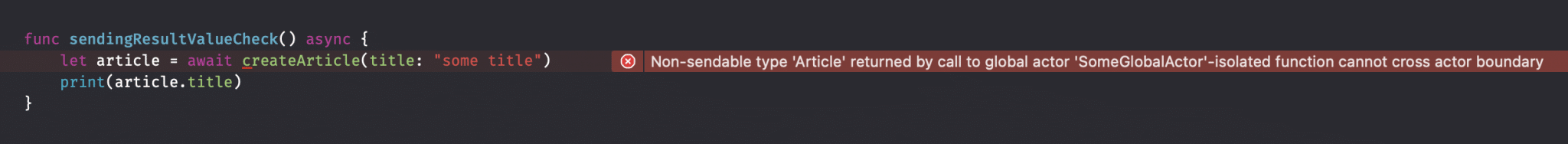

The method is attributed with a global actor, which means it will switch isolation domains. Calling this method results in a compiler error:

This is unfair since we know the constructed article is directly sent to the caller’s region. In other words, we know there’s no risk of a data race here.

We can solve this by using the sending keyword before the result type:

@SomeGlobalActor

func createArticle(title: String) -> sending Article {

return Article(title: title)

}

Once again, we’re sending ownership, we enforce an ownership transfer. The region-based checks will happen inside the callee’s region.

Summary

Region-based isolation prevents unnecessary compiler errors for non-sendable types that will never result in data races. It’s essential to understand this concept as it allows you to better understand why you’re sometimes not required to use Sendable or @Sendable.

In the next lesson, we’re going to look at concurrency-safe global variables.