Ensuring thread-safetyness also ensuring synchronized data access. When only a single isolation domain is able to access a mutable property at the same time, we prevent a so-called data-race from happening. Data races occur when multiple threads access shared mutable state when at least one of them performs a mutation.

Yet, data races are different from race conditions. The latter might actually not be solved by Swift Concurrency at all, so it’s important to know the differences and the impact of concurrency.

What is a data race?

A data race happens when multiple threads access shared memory concurrently without proper synchronization, causing undefined behavior. Code that seems to work can still be vulnerable to data races and unexpected crashes.

For example, this piece of code:

var counter = 0

let queue = DispatchQueue.global(qos: .background)

for _ in 1...10 {

queue.async {

counter += 1

}

}

print("Final counter value: \(counter)")

At first, it might look perfectly fine. However, two different threads are accessing the counter property while one is a write. This could be a potential data race.

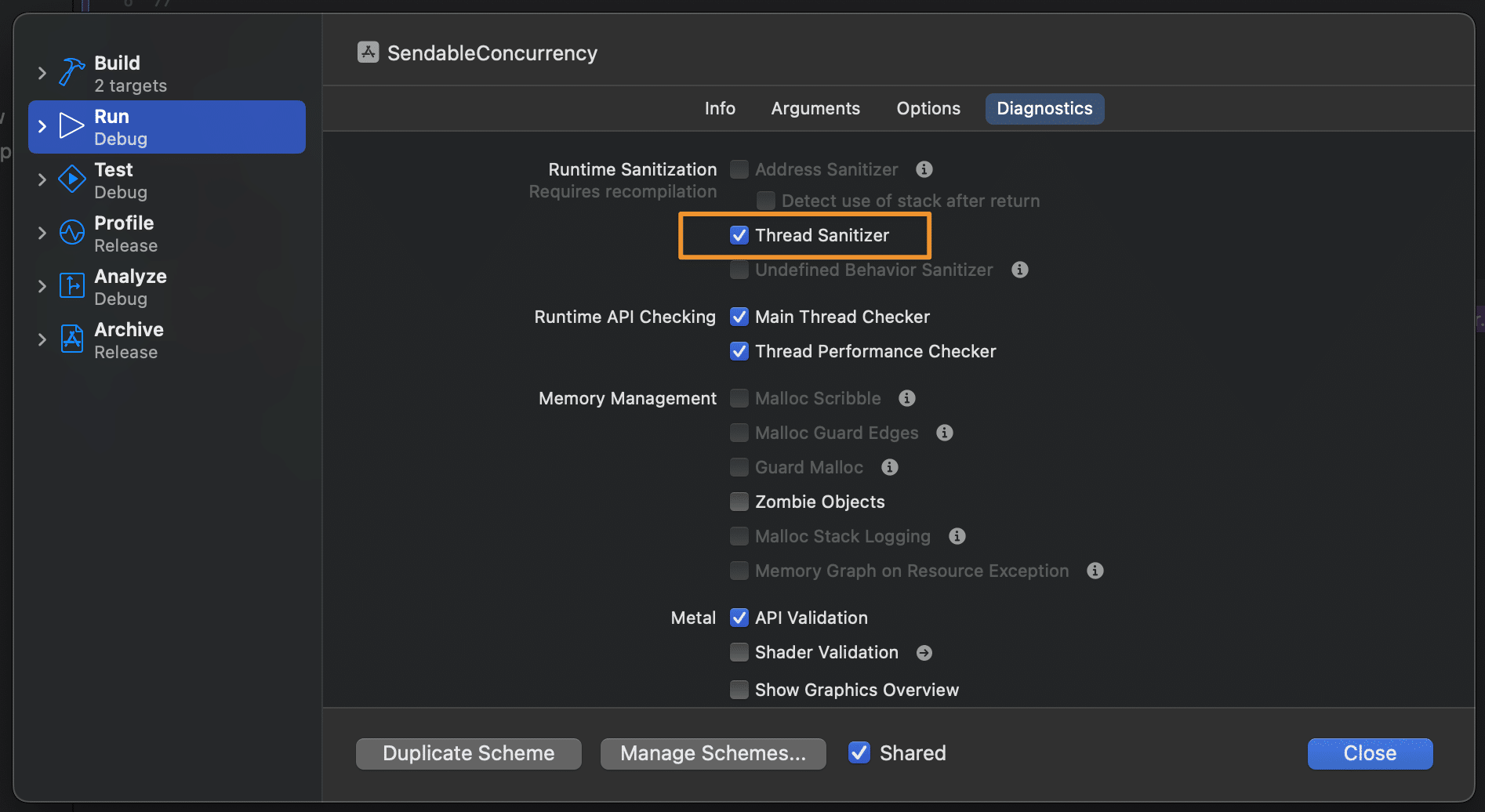

To confirm this, we can enable the Thread Sanitizer in our scheme settings:

The Thread Sanitizer allows us to find potential data races in our code.

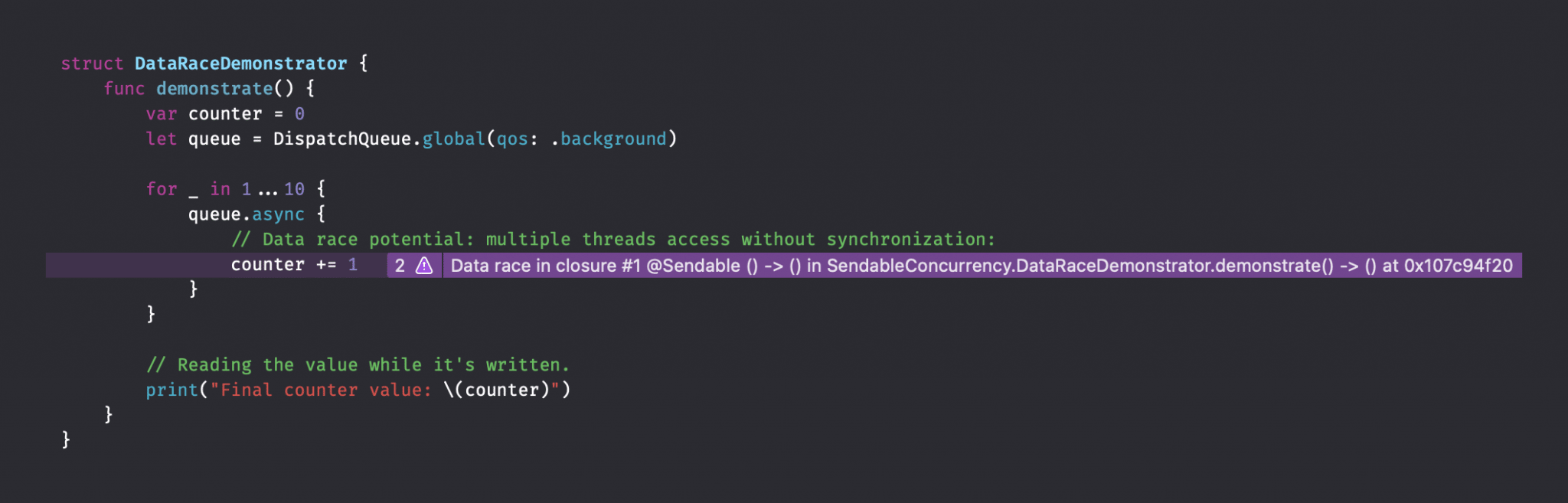

After running the app with the Thread Sanitizer enabled, we’ll notice a purple warning showing up:

A data race has been detected by the Thread Sanitizer.

A data race is challenging for several reasons:

- Determining the need for synchronization can even be challenging

- Worst of all: unsafe code does not guarantee to fail at runtime

- These runtime issues are hard to reproduce

I’ve had many crashes that were hard to understand and tough to reproduce. It’s very likely they’ve been the result of a data race.

Preventing data races using Swift Concurrency

With the above example in mind, we can demonstrate how Swift Concurrency prevents data races. But before we do, I first want to show how you could’ve potentially solved it using GCD:

var counter = 0

let serialQueue = DispatchQueue(label: "com.example.serial")

for _ in 1...10 {

serialQueue.async {

counter += 1

}

}

serialQueue.async {

print("Final counter value: \(counter)")

}

We’re now using a serial queue, synchronizing access to the counter property. This solves the potential data race, but we still need to remind ourselves to always use serialQueue.async to access the counter property. Nothing is stopping us from directly reading or writing the counter property.

A similar implementation using Swift Concurrency could look as follows using a new Counter actor:

actor Counter {

private var value = 0

func increment() {

value += 1

}

func getValue() -> Int {

return value

}

}

The actor creates a new isolation domain and prevents a data race by restricting access. The mutation logic would look as follows:

let counter = Counter()

for _ in 1...10 {

await counter.increment() // Safely increments the counter

}

/// Safe read using `await`

print("Final counter value: \(await counter.getValue())")

There’s no way for another isolation domain to access the counter-isolated properties without using await.

What is a race condition?

Now that we’ve seen how data races work, how they can be detected, and solved, it’s time to look into race conditions. A race condition occurs when multiple threads access shared data concurrently, leading to unpredictable behavior due to the timing of their execution. It often results in inconsistent or incorrect outcomes if proper synchronization mechanisms aren’t used.

For example, imagine rewriting the above code example by using a new Task around each increment:

let counter = Counter()

for _ in 1...10 {

Task {

await counter.increment() // Safely increments the counter

}

}

/// Safe read using `await`

print("Final counter value: \(await counter.getValue())")

The code compiles fine, Swift Concurrency is happy. However, if we run this code multiple times using the sample code project, we will have inconsistent results:

Final counter value: 10

Final counter value: 10

Final counter value: 6

This is because we’re dealing with a race condition. Each increment performs asynchronously and there’s no guarantee that all increments complete before we read out the final counter value. This is an important detail to be aware of as they could lead to flaky tests or inconsistent behavior.

Summary

While Swift Concurrency helps us prevent data races, we still need to be aware of race conditions that can occur. Yet, we’re in a much better place compared to GCD as we’ll be instructed at compile-time when we’re about to introduce a data race. In fact, with Swift Concurrency and actors, there’s no way we can access mutable state inside an actor domain without synchronization.

A type that ensures safe access to mutable state can be defined as sendable, and that’s exactly what this module is about. In other words, by defining something as sendable, we instruct the compiler about values that are safe to be accessed from any isolation domain. With this in mind, you’re ready to dive deeper into defining types as sendable. In the next lesson, I’ll introduce you to the Sendable protocol.