Now that we’ve had a brief introduction into the Sendable protocol, it’s time to dive into details on how you can make value types sendable. This lesson is part of a collection of lessons that should be useful to reference whenever you run into trouble along the way of making types sendable.

What are Value Types?

In Swift, value types are data types where each instance keeps a unique copy of its data. When a value type is assigned to a variable or passed to a function, Swift creates a copy rather than sharing a reference to the same instance. This behavior protects value types from unintended side effects, as modifications to one instance do not affect another.

This behavior impacts the sendability of types as they’re much more likely to be thread-safe by default. Yet, as with all types that want to conform to the Sendable protocol, all members and associated values must be sendable.

Examples of value types in Swift are:

- Structs

- Enumerations (enums)

- Tuples

- Basic data types like

Int,Double,Bool, andString

Structures and enumerations can implicitly conform to Sendable

In some cases, you don’t have to do anything to mark a value type as Sendable. They will be implicitly conforming to Sendable in the following cases:

- Structs and enums that aren’t public and aren’t marked with

@usableFromInline - Frozen structures and enumerations, even if they’re public

For example, imagine the following structure:

struct Person {

var name: String

}

While not marked explicitly as Sendable, it can be used across boundaries without any compiler errors:

struct SendableChecker: Sendable {

let person = Person(name: "Antoine")

func check() {

Task {

/// A compiler error will show up here if `person` isn't `Sendable`.

print(person.name)

}

}

}

Note

I’ve created this SendableChecker to easily validate sendability of types. You can find it in the sample code for this module.

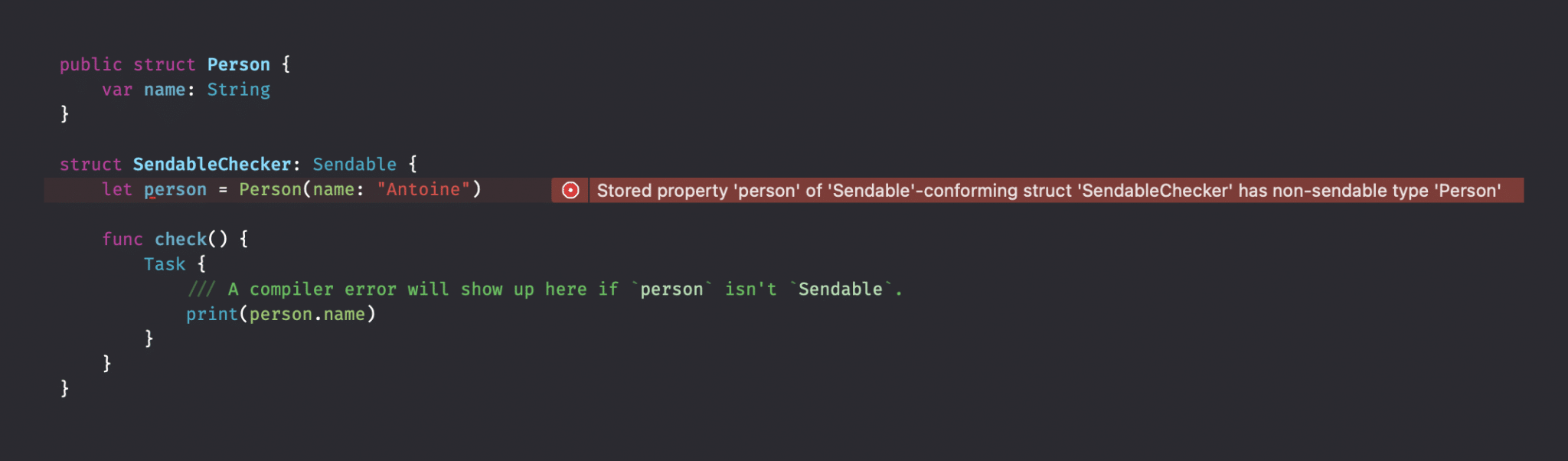

However, as soon as we mark Person as public, we will get a compiler error:

The SendableChecker allows to validate whether a type is sendable by sharing it across isolation domains.

At first, it might seem like the compiler should be able to tell whether a public struct is Sendable, especially since its stored properties can’t be changed outside the module. However, when compiling a module for use elsewhere (like in a library or framework), Swift hides internal details like private properties. That means the compiler can’t safely check whether all parts of the type are thread-safe. To avoid guessing, Swift requires you to explicitly mark public types as Sendable if you want to guarantee they’re safe to use across threads.

How @usableFromInline influences implicit conformance

When Swift determines implicit Sendable conformance for a type, it requires all stored properties themselves to be Sendable, and the type’s layout must not be visible outside the module.

However, if you mark a type as @usableFromInline, the type layout and details are effectively visible to other modules (because the type may be inlined), so Swift no longer treats it as purely internal. This stricter visibility means:

- The compiler is no longer allowed to implicitly assume internal types and properties won’t be shared across concurrency boundaries.

- Thus, implicit

Sendableconformance will be denied unless you explicitly confirm that the type is safe.

Why public frozen structs and enums can still get implicit Sendable conformance

When a struct or enum is marked as public, Swift does not automatically provide implicit Sendable conformance. This is because the compiler cannot assume that the type’s layout will remain the same in future versions — you might add new stored properties later that are not Sendable, which could compromise safety guarantees. Therefore, public types require explicit Sendable conformance unless the compiler can fully analyze and trust their structure.

However, when you mark a type as @frozen, you guarantee that its layout and cases will stay the same in future releases. This allows the compiler to fully examine all stored properties or related values and ensure they are Sendable. If they are, Swift can automatically infer Sendable conformance. That’s why public frozen structs and enums can still receive implicit Sendable conformance, even though they are externally visible.

Why public non-frozen enums aren’t implicitly Sendable (even though no one else can add cases)

Even though no one outside your module can add new cases to your public enum, Swift still does not automatically make it Sendable if it isn’t marked as @frozen. This is because, as the library author, you might decide to add new cases or change associated values in future versions of your library. Swift’s library evolution model lets clients compile against version 1 of your library and then, at runtime, link against a newer version without recompiling. If you add a new case later, client code compiled against the original version could encounter a case it doesn’t recognize, which breaks safety guarantees.

Marking an enum as @frozen explicitly informs the compiler and your clients that no new cases will ever be added. This enables Swift to fully understand the type’s structure and safely infer Sendable if all cases and associated values are themselves Sendable. Without @frozen, Swift cannot make this guarantee and thus requires you to declare Sendable conformance explicitly. This approach guarantees that concurrency safety is maintained even as libraries evolve.

Explicitly adding Sendable conformance

The above example is simply solved by adding explicit Sendable conformance:

public struct Person: Sendable {

var name: String

}

Nothing changed regarding internal structure; we only took over the responsibility of marking the type as sendable.

The above structure is relatively simple, and since we benefit from copy-on-write (COW), the structure becomes thread-safe and sendable even though the name is mutable! This is because any mutation will happen on a new copy of Person, ensuring there will never be a mutation of the same instance from a different thread simultaneously with a read. In other words, there’s no risk of data races.

All members need to be Sendable

For a type to be sendable, all members must also be sendable. Imagine adding another property to Person for a type that’s not yet marked as Sendable:

public struct Person: Sendable {

var name: String

var hometown: Location

}

public struct Location {

var name: String

}

We would run into the following compiler error:

Once again, Location does not implicitly conform to Sendable due to being marked as publicly available. Since we added a dependency to Location via the hometown property, our Person suddenly no longer becomes sendable.

In other words, you’ll have to take care of making all members sendable:

public struct Person: Sendable {

var name: String

var hometown: Location

}

public struct Location: Sendable {

var name: String

}

Restructuring code to simplify sendability

While the above example allowed us to modify Location and make it Sendable, you might also run into cases where you cannot add Sendable conformance. As we’ve learned in the previous lesson, you must add sendable conformance within the same file.

If the Location structure had been defined inside a third-party dependency, you would have to come up with another solution. One way would be to use @unchecked Sendable (more on that later), but you can also look at how the type is being used.

For example, we could decide to not capture a reference to the Location type itself but only the name of the location:

public struct Person: Sendable {

var name: String

var hometown: String

init(name: String, hometown: Location) {

self.name = name

self.hometown = hometown.name

}

}

public struct Location {

var name: String

}

This way, we don’t have to make Location sendable, but we can still use its value inside our Person structure.

Making a type sendable by using an actor

Another way of marking a type as sendable is by synchronizing access via a given actor. This can be useful in cases where you know for sure access needs to happen via such an actor. We’ll dive deeper into actors in a dedicated module later in this course, but for now, I want to introduce you already to the @MainActor attribute. This actor ensures your code is accessed via the main thread only and can be useful for things like view elements or view models.

For example, the following view model would not be Sendable since its location member isn’t sendable either:

public struct Location {

var name: String

}

struct LocationDetailViewModel {

let location: Location

}

Yet, if we would mark it with the @MainActor attribute, we implicitly add conformance to Sendable due to the actor isolation domain:

public struct Location {

var name: String

}

@MainActor

struct LocationDetailViewModel { // Implicitly conforms to Sendable now.

let location: Location

}

Due to the actor, access can only happen via the actor’s isolation domain. The actor prevents data races, so LocationDetailViewModel becomes thread-safe. This also takes away the requirement for all members to be sendable.

Once again, this is just a brief introduction into actors. We’ll go deeper into details in a dedicated module where we will also discuss best practices on using @MainActor to add sendable conformance.

Making enums conform to Sendable

Enumerations work similarly to structures in that implicitly conformance rules apply and all members need to be sendable for the type itself to become sendable.

Imagine the following enum for a person’s role:

public enum PersonRole: Sendable {

case student

case employee(company: String)

case retired(yearsOfService: Int)

case unemployed

}

Since it’s a public enum, we must explicitly add Sendable conformance. All of the associated values like company and yearsOfService are sendable too, so the above type is safe to use on our early defined Person:

public struct Person: Sendable {

var name: String

var hometown: String

var role: PersonRole

init(name: String, hometown: Location, role: PersonRole) {

self.name = name

self.hometown = hometown.name

self.role = role

}

}

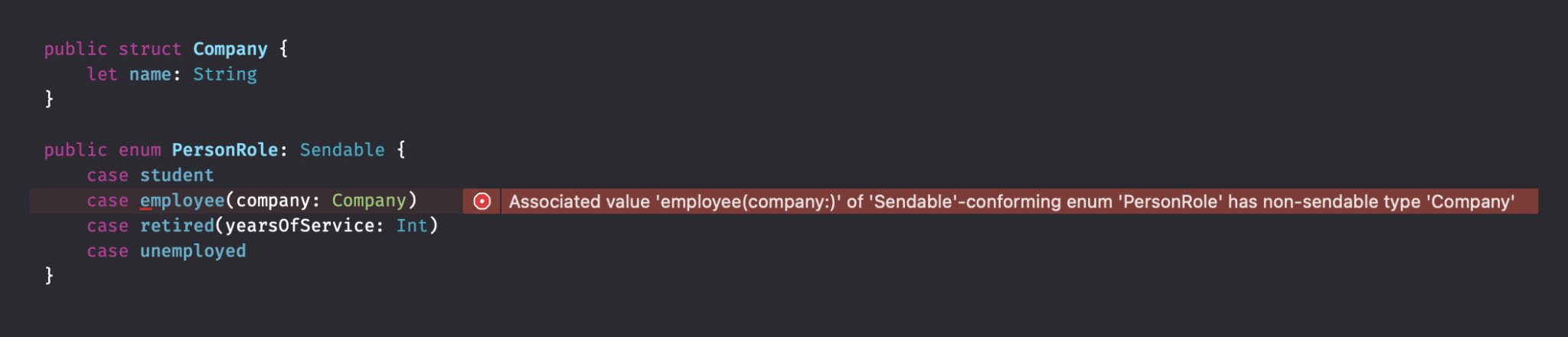

However, as soon as we add a non-sendable associated value, we will run into a compiler error:

All members need to be sendable before a type itself can be sendable.

Once again, just like with structures, all members must be sendable for the type to become sendable. Therefore, we can solve this by explicitly marking Company as sendable:

public struct Company: Sendable {

let name: String

}

public enum PersonRole: Sendable {

case student

case employee(company: Company)

case retired(yearsOfService: Int)

case unemployed

}

Summary

Value types benefit from copy-on-write, which makes it easier to define these types as thread-safe. This is as long as the compiler can keep all members visible, which will not be the case if types are marked as public. In those scenarios, you must add explicit conformance to Sendable within the same file.

Classes are reference types and can be used as abstract classes. These are a bit more challenging and we’ll dive into the details in the next lesson.