While some of the principles of value types apply to reference types, a few key differences make reference types more challenging when it comes to sendable. There’s no implicit conformance unless an actor is used. More differences will be discussed in this lesson.

What are reference types?

Reference types are objects that are shared across different parts of your code. Instead of copying the entire object when assigning it to a new variable, Swift only creates a new reference to the same instance in memory. This means that when one part of your code modifies the object, all other references see the change immediately.

There are different forms of reference types in Swift:

- Classes (class)

- Closures (() -> Void)

- Actor (actor)

- Metatypes (Type & AnyClass)

- Protocols with class or AnyObject Constraints

- NSObjects (Objective-C Reference Types)

- References through UnsafePointer & Unmanaged

Let’s look at an example of a class:

class Counter {

var value: Int = 0

}

Which we could use as follows:

let firstCounter = Counter()

/// Creates another reference to the same object:

let secondCounter = firstCounter

/// Even though we increment `secondCounter` only:

secondCounter.value += 1

/// `firstCounter` changes as well since we use the same object reference:

print(firstCounter.value) // 1

Even though value was changed through secondCounter, firstCounter also reflects the change. That’s because both variables point to the same instance of Counter. Unlike value types, reference types don’t have independent copies, which makes them more complex to use in concurrent code.

Since reference types allow shared access, they can introduce data races and race conditions when used across multiple threads. This is why adding Sendable conformance when working with reference types is even more essential to ensure safe and predictable behavior.

Marking a class as Sendable

While we can mark many structures and enumerations as Sendable by just adding the Sendable protocol inheritance, classes are much more challenging.

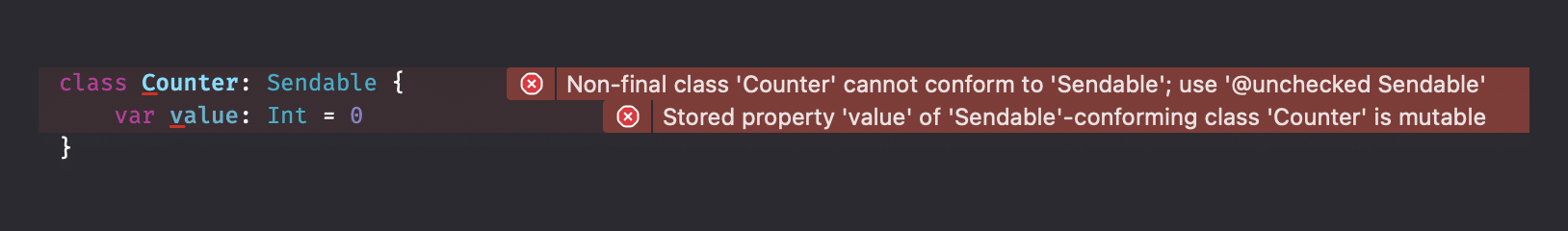

The above Counter example cannot simply be marked as Sendable as follows:

Marking a class as Sendable isn’t as easy as with value types.

The first challenge is dealing with non-final classes (we handle that later) and the second one is about the mutable member. However, if you remember correctly, we didn’t had this issue if we used a structure instead:

/// This compiles fine:

struct Counter: Sendable {

var value: Int = 0

}

This is because our Counter class creates references to the same underlying data. In other words, multiple isolation domains will potentially access the same underlying piece of data with a risk of data races.

To successfully implement all the requirements of the Sendable protocol, a class must:

- Be marked

final - Contain only stored properties that are immutable and sendable

- Have no superclass or have

NSObjectas the superclass

In all other cases, you’ll have to add synchronized access to mutation via internal locking mechanisms in combination with @unchecked Sendable or by using an actor.

In the above example, it makes perfectly sense to adjust the Counter into an actor:

actor Counter {

var value: Int = 0

}

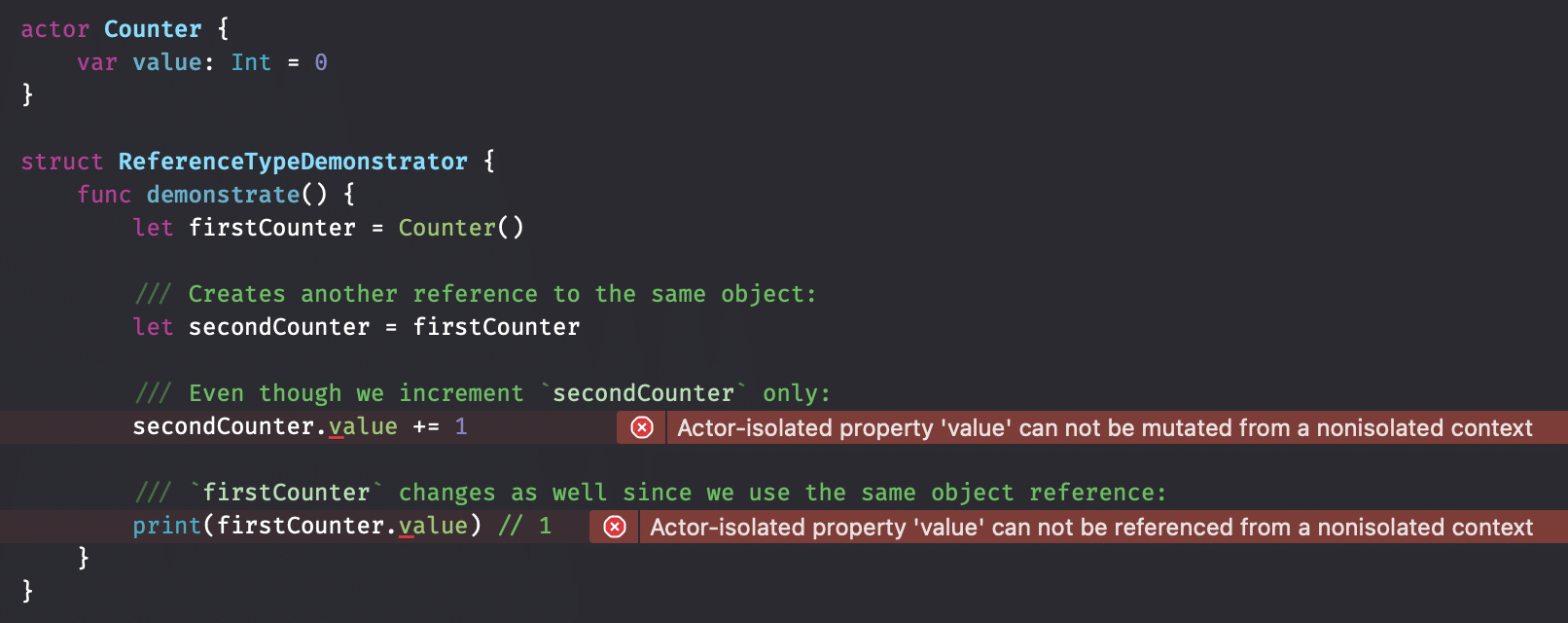

This makes the type automatically Sendable, as all access will be synchronized via the actor’s executor. However, this could lead to a so-called concurrency rabbit hole as you’ll suddenly have to deal with concurrency in nonisolated contexts:

An actor requires asynchronous access and can’t be used directly from a nonisolated context.

This can be annoying if you aim to ‘just solve the data race’, but it is required to deal with to ensure your code becomes thread-safe at compile time. Before going the actor route, you can ask yourself the following questions for an alternative:

- Can I make this class a structure instead?

- Does this class need to be mutable and non-final?

- Is this class mainly used from the main thread and should it be marked with

@MainActorinstead?

This could lead to a more straightforward solution, depending on your use case. Many apps run mostly on the main thread, and if our Counter would only be used inside SwiftUI views, we could decide to mark it with @MainActor instead:

@MainActor

class Counter {

var value: Int = 0

}

Understanding how non-final classes can’t be Sendable

As mentioned before, non-final classes can’t be marked as sendable. This is because a child class could introduce mutability, breaking the sendable contract.

For example, the following class would be sendable in theory:

class Purchaser {

func purchase() {

/// ... purchase logic

}

}

It does not contain mutable members, so there is currently no risk of data races. However, it can still be used as a parent of a child class that introduces unsafe mutability:

class GameCreditsPurchaser: Purchaser {

var purchasedCredits: Int = 0

}

Due to this possibility, it’s impossible to make Purchaser sendable as long as it’s not defined as a final class.

Why isn’t it possible for the compiler to validate all abstract use cases?

You could argue that the compiler should be able to check all usages of Purchaser and throw an error as soon as one of the child classes introduces unsafe mutability. In theory, this is possible, but applying performance optimizations for optimized compilation would be much more challenging. Whole-module compilation would be required more often, leading to a degraded build performance.

Understanding the impact of a super class on sendability

In general, a sendable class cannot have a parent class. The only exception is NSObject. For example, you might have a type that conforms to CLLocationManagerDelegate which requires the type to conform to NSObjectProtocol:

/// Even though we use a parent class, we can mark it as `Sendable`.

/// This is only possible with `NSObject`.

final class LocationUpdatesReceiver: NSObject, CLLocationManagerDelegate, Sendable {

func locationManager(_ manager: CLLocationManager, didUpdateLocations locations: [CLLocation]) {

guard let location = locations.last else { return }

print("Updated location: \(location.coordinate)")

}

}

This is convenient in cases where you need to interact with Objective-C-based APIs.

Using composition to create Sendable reference types

You’ll likely run into scenarios where you have existing code that’s based on classes, making it harder to migrate to Sendable. The earlier mentioned Purchaser class is a great example.

We can benefit from composition to solve this accordingly. It allows us to mark each purchaser as final while still benefiting from reference types. Instead of using Purchaser as an abstract class, you would use it as a member of GameCreditsPurchaser:

final class Purchaser: Sendable {

func purchase() {

/// ... purchase logic

}

}

final class GameCreditsPurchaser {

var purchasedCredits: Int = 0

let purchaser: Purchaser = Purchaser()

}

We would still need to deal with purchasedCredits to make GameCreditsPurchaser sendable too, but we at least have a better solution to keep using Purchaser, marking it as Sendable, while not having to apply too many code changes.

However, as always, it’s even better to consider a structure instead of a class. Our Purchaser currently only comes with a single method, so it would be more than fine to make it a struct that implicitly conforms to Sendable:

struct Purchaser {

func purchase() {

/// ... purchase logic

}

}

Summary

In this lesson, we’ve looked into making reference types conform to Sendable. They’re more challenging than value types as we are dealing with shared memory by default. Unless you can make a class actor isolated, it can be quite challenging to make a class sendable. Therefore, it’s always good to consider whether it’s possible to use a struct instead of a class or refactor towards composition.

In the next lesson, we’re going to look into using @Sendable with closures.