Now that we know why we need to mark objects as sendable, it’s time to put things into practice. In the following lessons, we’ll dive deeper into how you can mark classes, structures, and other types as Sendable.

This lesson is an introduction to the Sendable protocol and will give you a better understanding of how the protocol works and how it’s evaluated.

An introduction to the Sendable protocol

The Sendable protocol is a special protocol that indicates to the compiler that a type is thread-safe. Such type can be shared across isolation domains without introducing a risk of data races.

The protocol definition is quite boring:

public protocol Sendable {

}

It seems that you’re not required to implement any protocol conformances, but the opposite is true. Once your type inherits this protocol, the compiler will verify whether there’s any unprotected mutable state. For example, we might have a view model for a person detail view:

class PersonDetailViewModel {

var personName: String = ""

init(personName: String) {

self.personName = personName

}

}

This type currently belongs to the nonisolated domain and no concurrency checking will take place when building in Swift 6 language mode. However, as soon as we add the Sendable protocol conformance, we will run into the following compiler feedback:

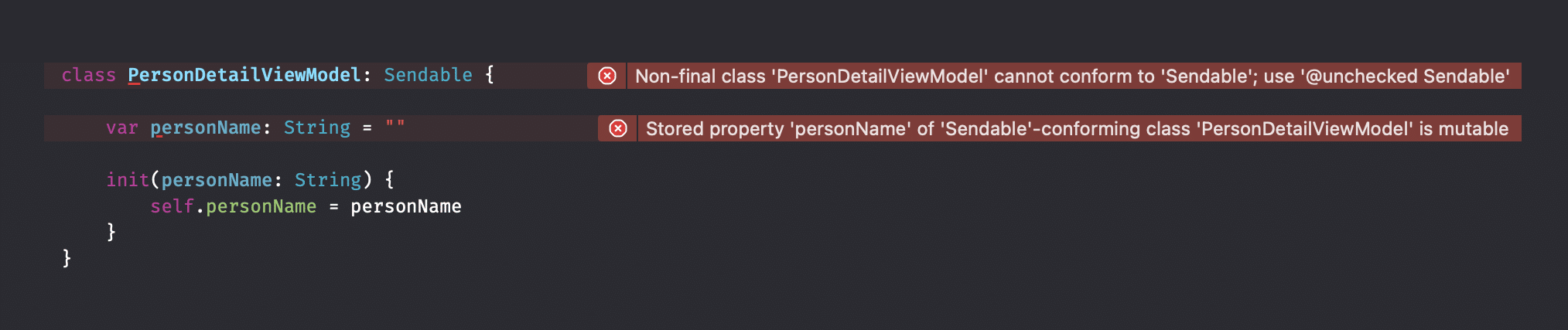

A simple example of a class that just added the Sendable protocol inheritance.

The compiler checks whether the PersonDetailViewModel is safe to pass around threads and concludes:

- It’s a non-final class, which means it could be used as an abstract class. Descendants could introduce unprotected mutability, so it’s unclear whether this type is thread-safe.

- The property

personNameis defined as avar, which indicates it’s mutable. Since a class is a reference type, it can be mutated from any thread. The mutation is not protected via a lock, so this is another sign that the type isn’t thread safe.

These checks are all happening because we’ve added the Sendable protocol conformance. In the following lessons, we’ll dive deeper into how you can properly make different types conform to Sendable.

The types that can conform to Sendable

Any type that wants to conform to Sendable can’t have any shared mutable state, unless it’s protected by a locking mechanism or forced to be accessed from a specific actor. Only the latter can be enforced by the compiler while a locking mechanism will require you to use @unchecked Sendable (more about that in a future lesson).

Once marked as Sendable, you can pass the type safely around isolation domains. All of the following can be marked as sendable:

- Reference types with no mutable storage

- Reference types that manage access to their state internally (using locks, for example)

- Final classes with no mutable storage or with managed access to mutation

- Value types like structs or enums

- Functions and closures by marketing them with the

@Sendableattribute

Each of these come with their challenges and common use cases, which is why this course module will handle them one-by-one in dedicated lessons.

The restriction of conforming to Sendable in the same source file

A type’s conformance to Sendable must be declared in the same source file where the type is defined. This restriction exists because the compiler needs full visibility of all stored properties to verify that the type is safe to use across concurrency domains.

For example, consider the following type defined in a Swift package:

public struct Article {

internal var title: String

}

Here, Article is declared as public, but its title property is internal, meaning it isn’t visible outside the module. As a result, if you tried to add Sendable conformance from another file, the compiler wouldn’t be able to inspect title to ensure it is thread-safe, even though String itself is Sendable. By requiring conformance to be declared in the same file, Swift ensures that all properties are fully visible and can be checked for safety.

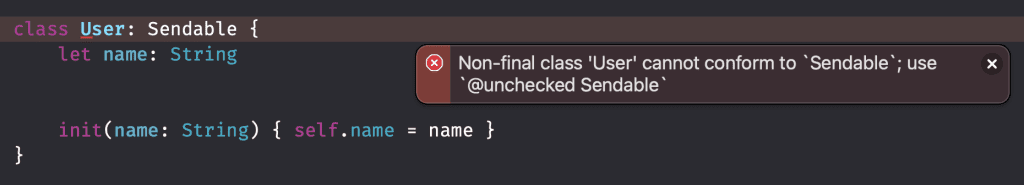

The same problem occurs when trying to conform an immutable non-final class to Sendable:

Non-final immutable classes can’t conform to Sendable

Since the class is non-final, we can’t conform to Sendable as we’re unsure whether other classes will inherit from User with non-sendable members. Therefore, we would run into the following error:

As you can see, the compiler suggests using @unchecked Sendable. We can add this attribute to our user instance and get rid of the error:

class User: @unchecked Sendable {

let name: String

init(name: String) { self.name = name }

}

However, this requires us to ensure it remains a thread-safe type whenever a new class inherits from User. As we add extra responsibility to ourselves and our colleagues, using this attribute is discouraged instead of using composition, final classes, or value types. We’ll dive deeper into @unchecked Sendable in one of the next lessons.

Summary

In this lesson, we’ve had a brief introduction into how the Sendable protocol works. While it’s an empty protocol, it does have semantic requirements that are enforced at compile time. For these requirements to be enforced, we need to conform to Sendable within the same module.

In the following lessons, we’ll dive deeper into case-per-case examples of conforming types to Sendable or using the @Sendable attribute. These lessons will be helpful throughout your concurrency journey as you can reference them specifically when running into challenging while making a type sendable.