Concurrency-safe global variables help you prevent data races and allow you to solve strict-concurrency-related warnings. Since you can access global variables from any context, ensuring access is safe by removing mutability or conforming to Sendable is essential.

We’ve learned our goal is to prevent data races and we can do so with the techniques learned in previous lesson for this module. However, there are cases where you’re running into global variables that are a little harder to make thread-safe.

What are global variables?

Before diving into the details for this lesson, it’s good to understand what we mean by global variables.

A global variable has a global scope, meaning it’s accessible and visible (hence accessible) from anywhere in your code. You’ve most likely used a global variable when working with a singleton:

struct APIProvider {

static let shared = APIProvider()

}

By using the static keyword, you can now access the shared variable from anywhere in your code:

struct ContentView: View {

var body: some View {

VStack {

Text("Hello, world!")

}

.padding()

.onAppear {

/// We can access the shared instance

/// using the `shared` variable.

APIProvider.shared.request()

}

}

}

The usage of global variables, particularly singletons, is often opinionated by developers in the community. Whether or not you decide to use them, it’s essential to think about concurrency-safe global variables since they’re accessible from anywhere in your code. This means it is accessible from different threads, as well as from async contexts. Therefore, it’s crucial to prevent data races.

Creating concurrency-safe global variables

If you’ve tried migrating to Swift 6 before, it’s likely that you’ve been running into the following compiler error:

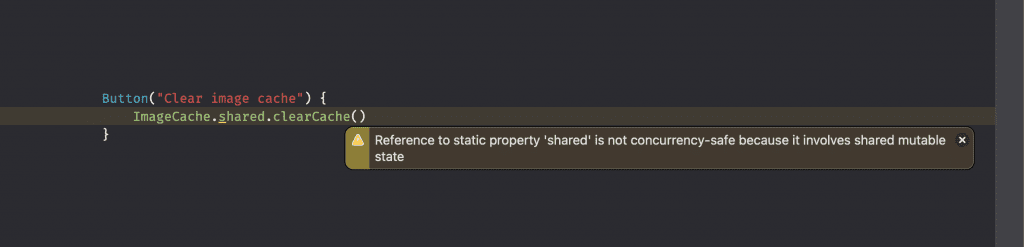

The following code is an example of where this warning would show up:

class ImageCache {

/// When you've enabled Swift 6 language mode:

/// Error: Static property 'shared' is not concurrency-safe because it is nonisolated global shared mutable state

static var shared = ImageCache()

}

Compared to the earlier shared code example of an API provider, we’re now dealing with a class called ImageCache and a mutable variable shared. The strict concurrency build setting will indicate unsafe access and show a warning accordingly:

Concurrency-safe global variables are required to conform to strict concurrency.

There are several ways of solving this warning. You could isolate the image cache using a global actor like @MainActor:

/// Isolated by the @MainActor, making is concurrency-safe.

@MainActor

class ImageCache {

static var shared = ImageCache()

func clearCache() {

/// ...

}

}

You can now only access the image cache from the main actor, making its access serialized and concurrency-safe. However, actor isolation might not always work since it complicates access from non-concurrency contexts. Another solution would be to make image cache both immutable and conform to Sendable:

/// The `ImageCache` is `final` and conforms to `Sendable`, making it thread-safe.

final class ImageCache: Sendable {

/// The global variable is no longer a `var`, making it immutable.

static let shared = ImageCache()

func clearCache() {

/// ...

}

}

As we’ve learned in previous lessons, we’ve had to do a few things to make our image cache class concurrency-safe:

- We’ve marked the class as

final, making introducing mutable states through inheritance impossible. This is required to make a class conform toSendable. - The

sharedvariable is no longer mutable since we’ve defined it as astatic let.

While either actor isolation or conforming to Sendable works in most cases, you might have global instances with a custom locking mechanism. There’s a way to opt out of concurrency checking for these cases.

Marking a global variable as nonisolated unsafe

You could be running into a scenario where you know your global variable is concurrency-safe, but you’re still running into strict concurrency-related warnings. This is similar to using @unchecked Sendable: you’re taking over ownership of ensuring thread-safe access.

An example could be a force unwrapped shared property which you initialize through a configuration method:

struct APIProvider: Sendable {

// Error: Static property 'shared' is not concurrency-safe because it is nonisolated global shared mutable state

static private(set) var shared: APIProvider!

let apiURL: URL

init(apiURL: URL) {

self.apiURL = apiURL

}

static func configure(apiURL: URL) {

/// We know this is the only mutation point for `shared`.

shared = APIProvider(apiURL: apiURL)

}

}

It’s better to rewrite this code and eliminate the forced unwrap global variable, but that’s not always possible when dealing with a large codebase. Secondly, you’re likely sure the configuration method is called directly at the app launch, not risking data races. In those cases, you can make use of the nonisolated(unsafe) keyword that was introduced in SE-412:

struct APIProvider: Sendable {

/// We've now indicated to the compiler we're taking responsibility ourselves

/// regarding thread-safety access of this global variable.

nonisolated(unsafe) static private(set) var shared: APIProvider!

}

It’s essential to realize this is not making your code thread-safe. You’re taking responsibility yourself to ensure you’re only calling the configure(apiURL: ) method in a way that does not result in any data races. I highly recommend marking your shared property private(set) to ensure mutation only happens within the same class. This makes it easier to manage concurrent access, helping you prevent data races accordingly.

Summary

Global variables allow you to access shared instances from anywhere in your codebase. With strict concurrency and Swift 6, we must ensure access to the global state becomes concurrency-safe by actor isolation or Sendable conformance. In exceptional cases, we can opt out by marking a global variable as nonisolated unsafe. Just like with @unchecked Sendable, it’s recommended to try to stay away from this unsafe solution if possible.

In the next lesson, we’re going to look into combining Sendable with custom locks.