In the previous lesson, we learned techniques to reduce suspension points. Applying these correctly from the get-go would be great, but the reality is that we will end up with situations in which we unnecessarily suspend a lot.

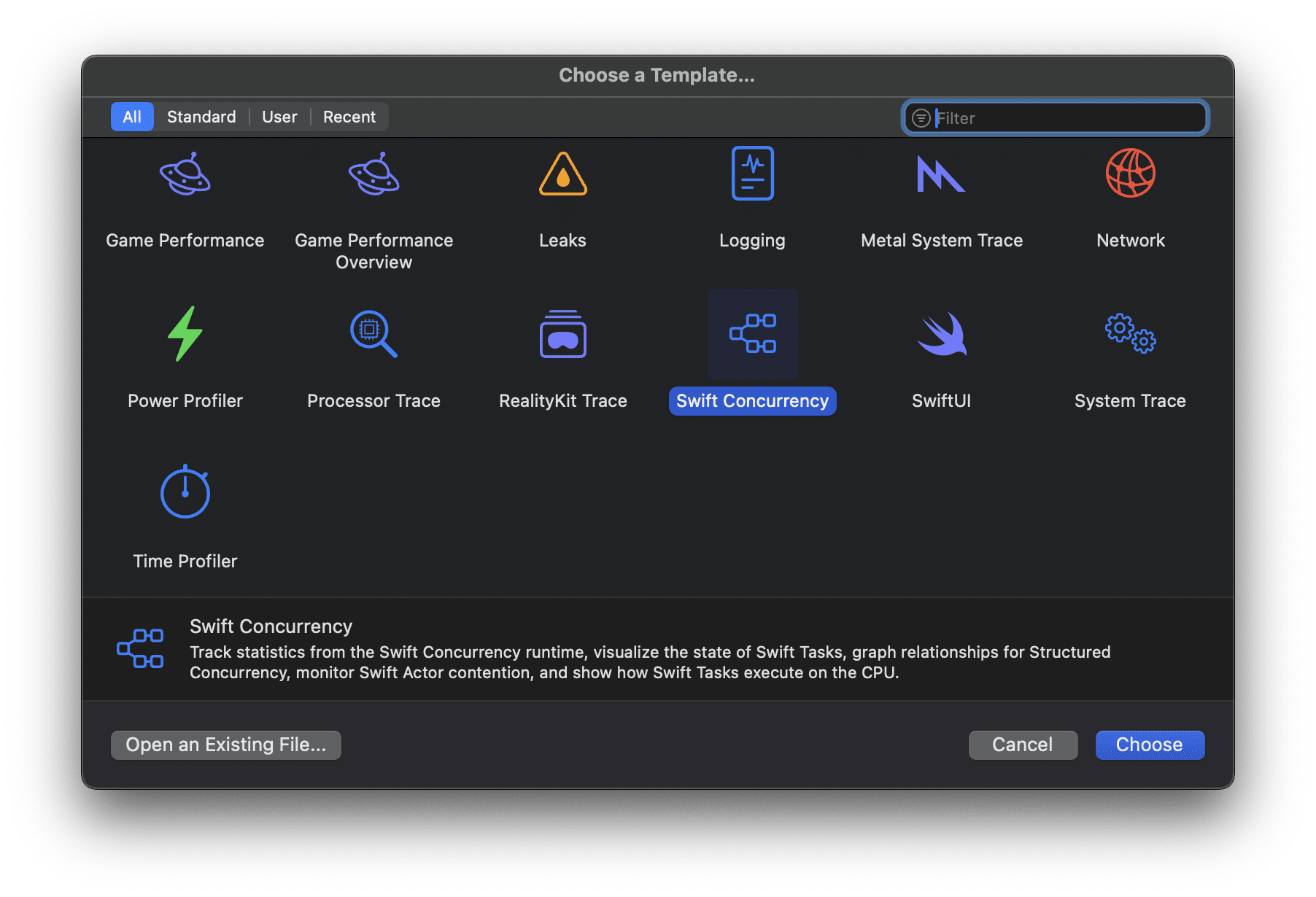

In this lesson, I’ll show you how to use Xcode Instruments to analyze suspension points for your apps. We will continue to use the same template as the first lesson, in which we analyzed our gradient generator app. If you’re starting fresh, make sure to profile the sample application by using the Swift Concurrency template:

Exploring Task States

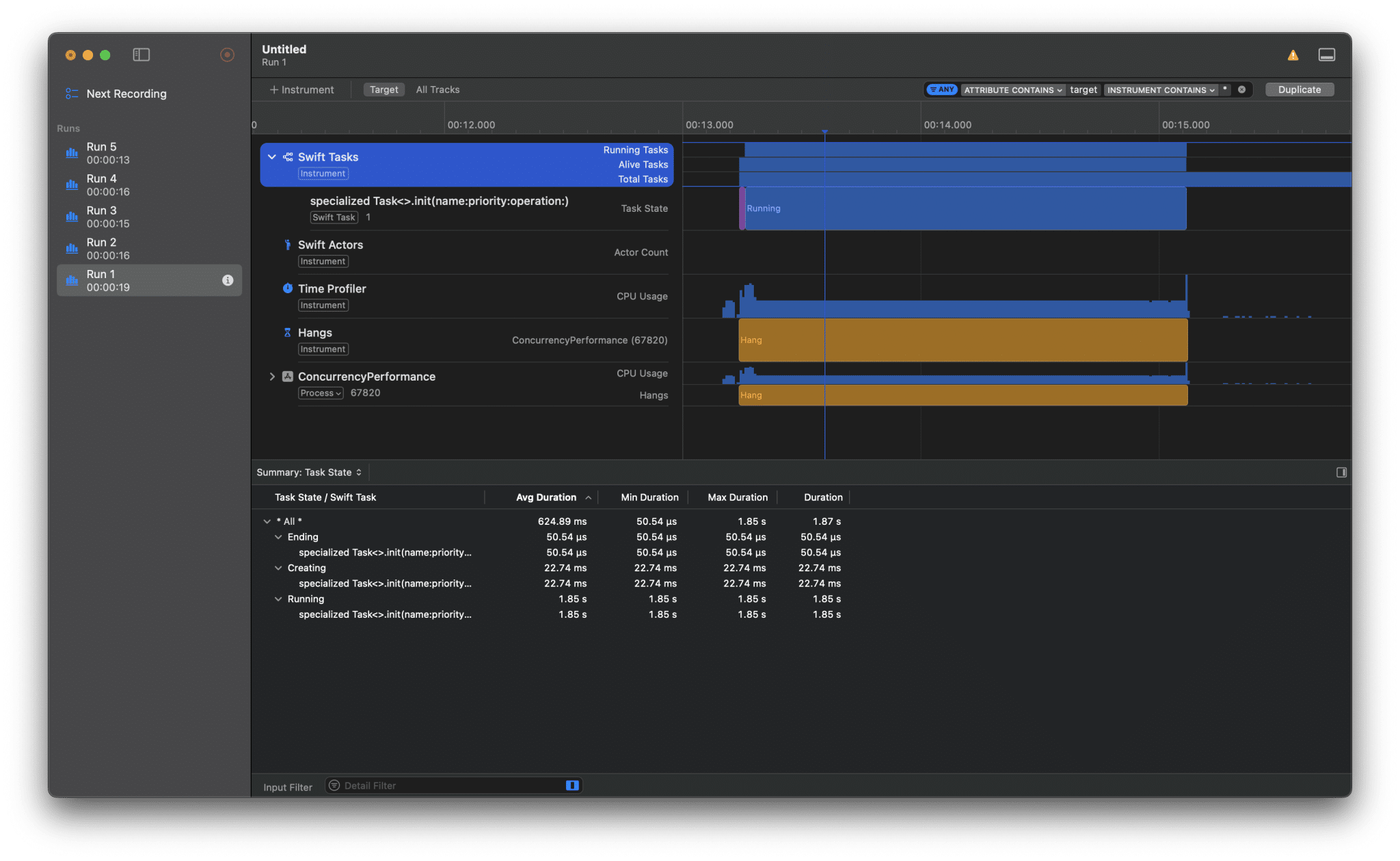

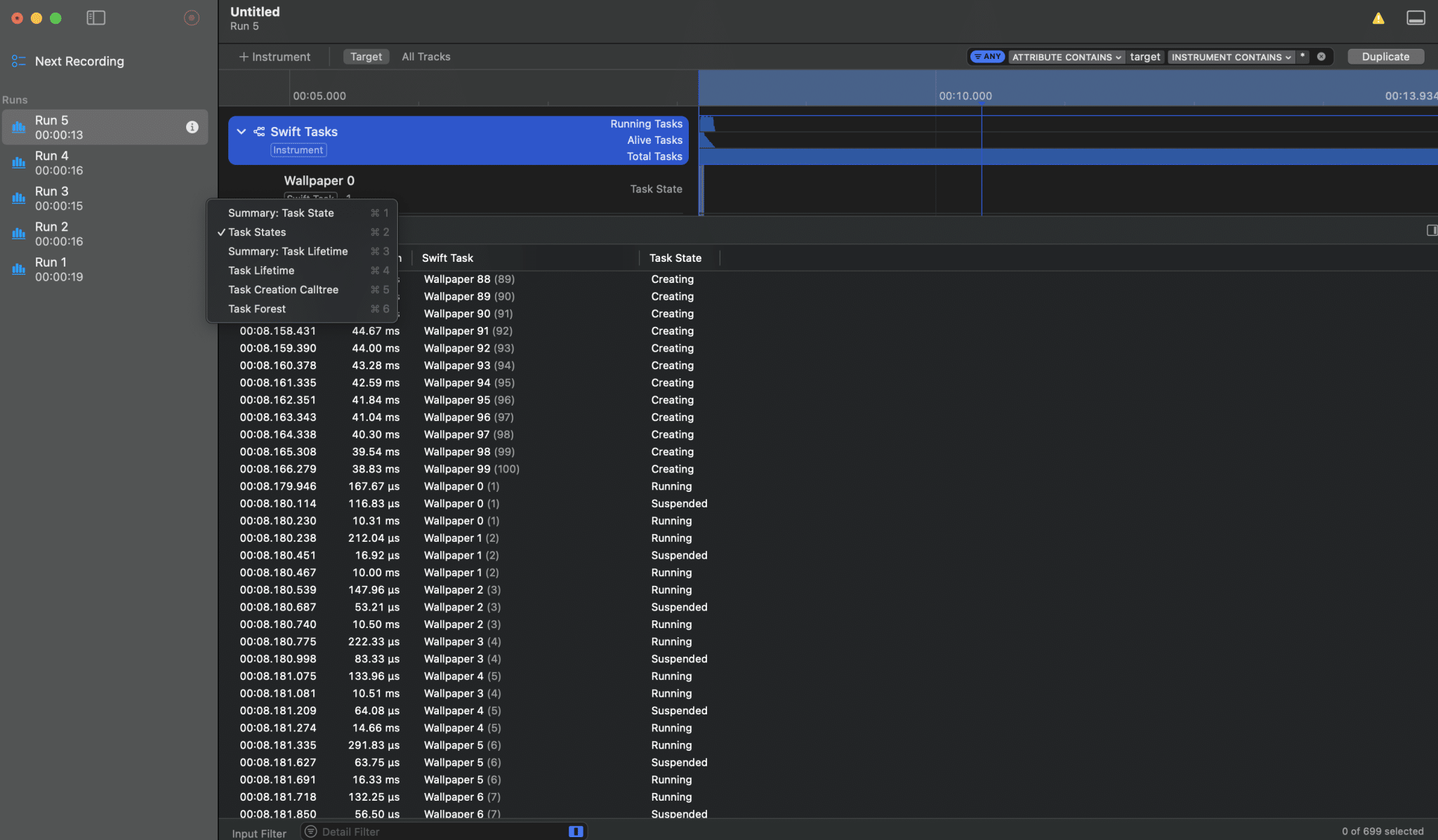

The gradient generator application improvements we’ve applied show great results in-between states to use in this lesson. The first version had no parallelism or asynchronous execution. We can validate this by looking into instruments by selecting the Swift Tasks instrument:

The summary at the bottom shows the different states of the tasks. There has only been a single task that had the Creating, Running, and Ending states.

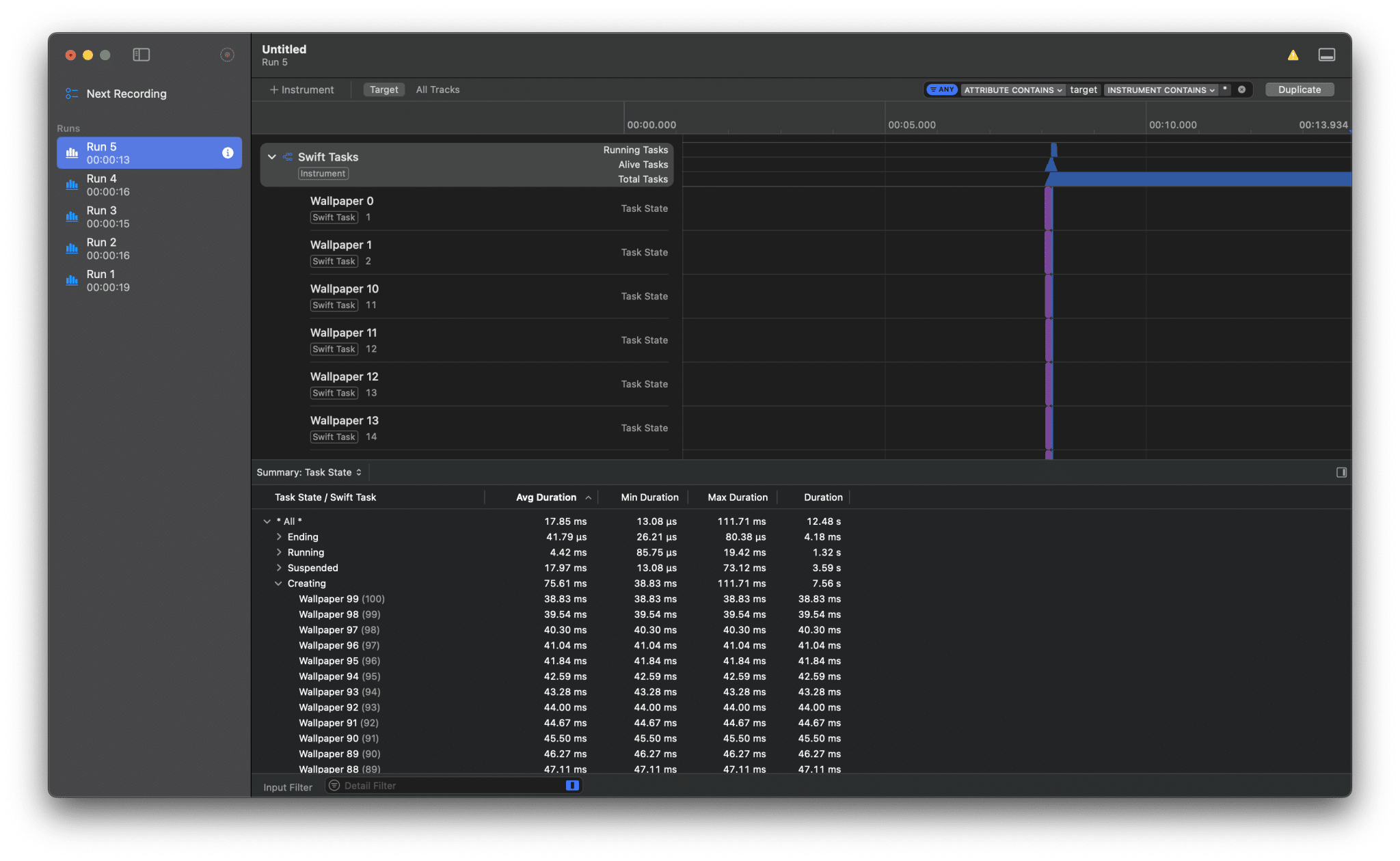

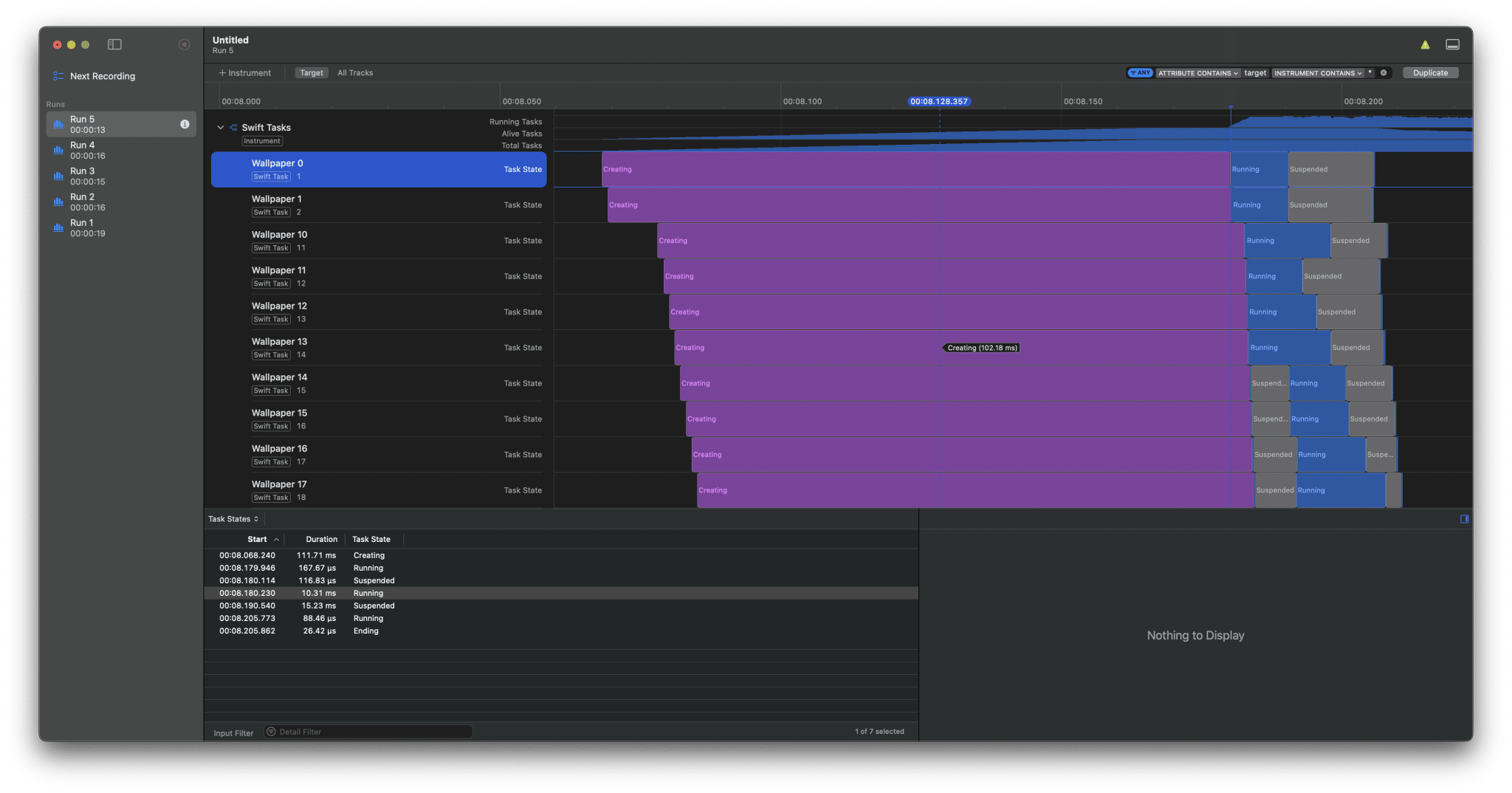

If we look at the final run, we can see many more tasks and states:

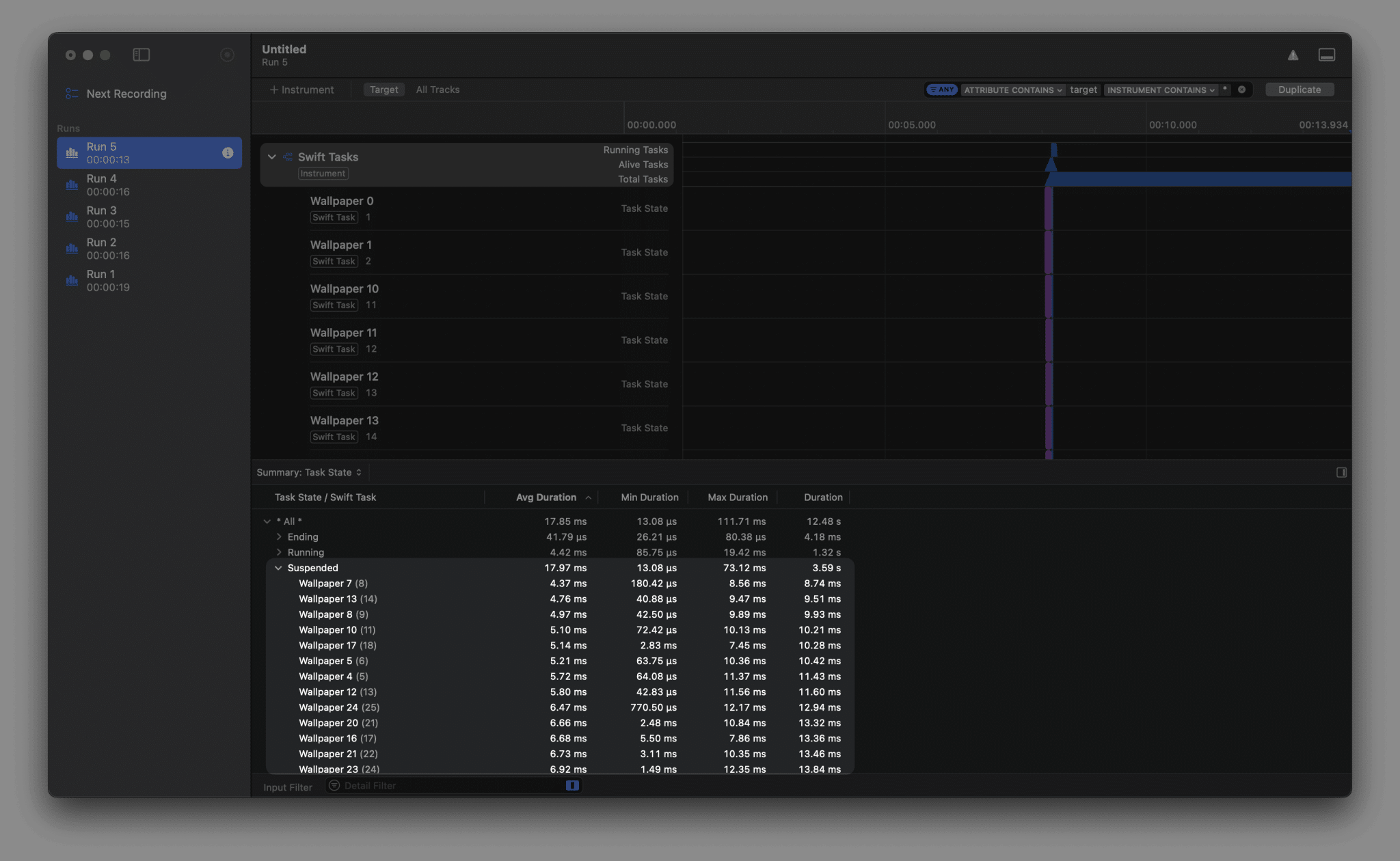

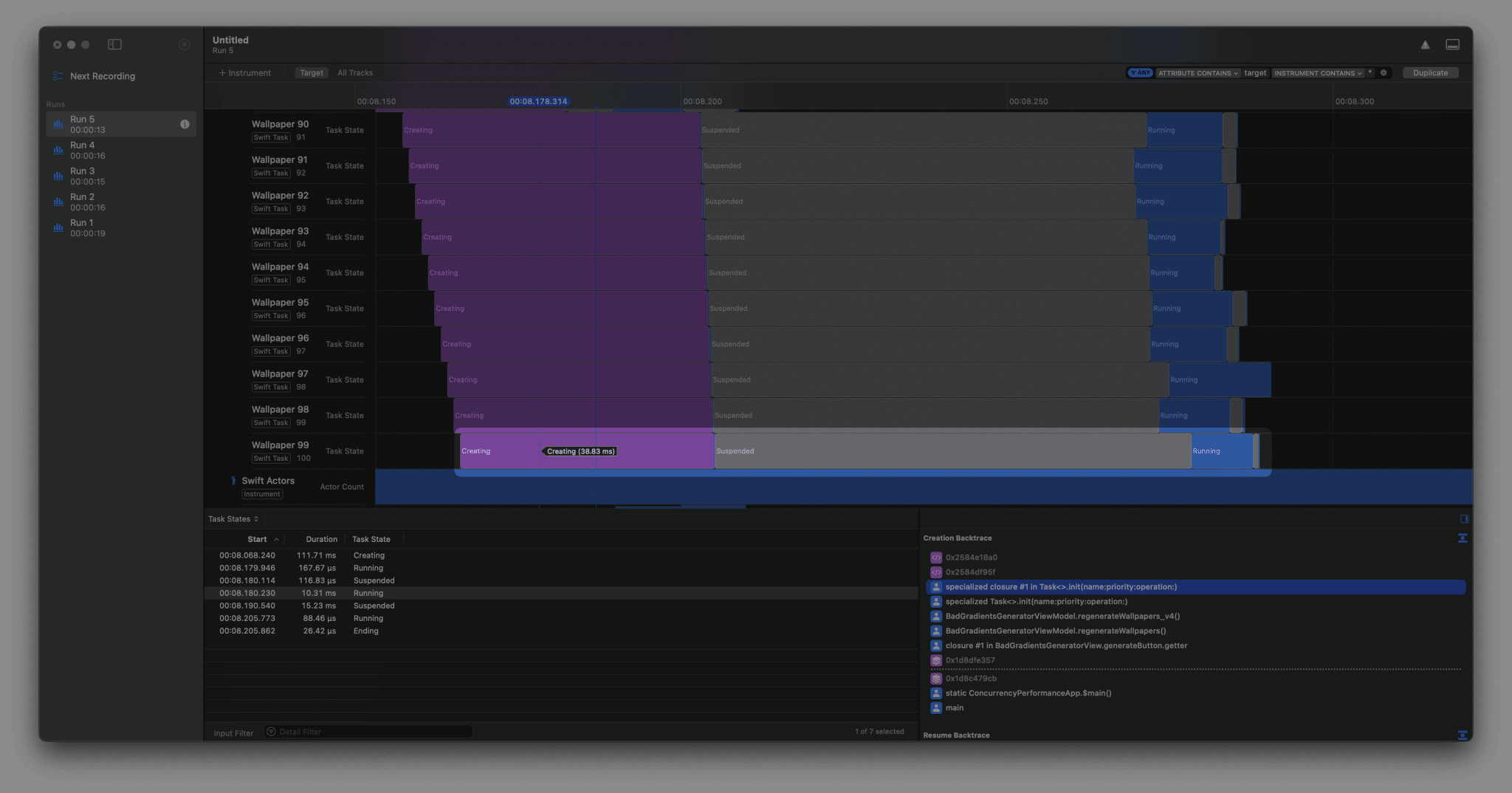

Since we’ve created a dedicated task for each wallpaper generation, we ended up with at least 100 tasks. What’s interesting, though, is that we have a new task state that we didn’t see in the first version: Suspended:

It’s also showing that we’ve been suspended for a total time of 3.59 seconds. This could mean that we can optimize our code to be 3.59 seconds faster. However, there’s also simply a limit on how many tasks can run at the same time.

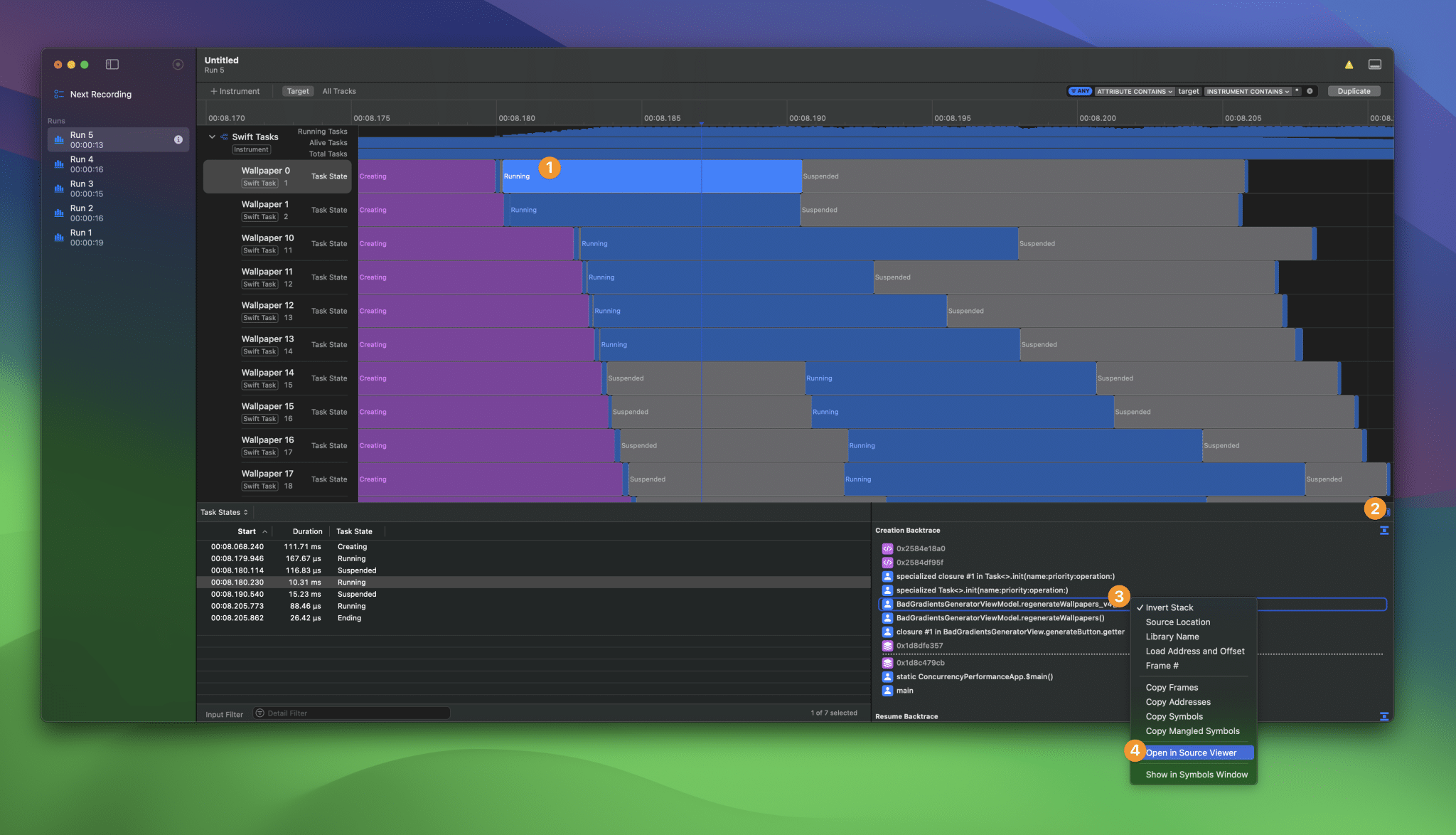

If we switch from summary to Task States we can see that all wallpaper tasks are created at the same time:

You can see this by looking at the Swift Task name and the Task State column to its right. All 100 wallpaper tasks get the state Creating before we end up with the first Running task.

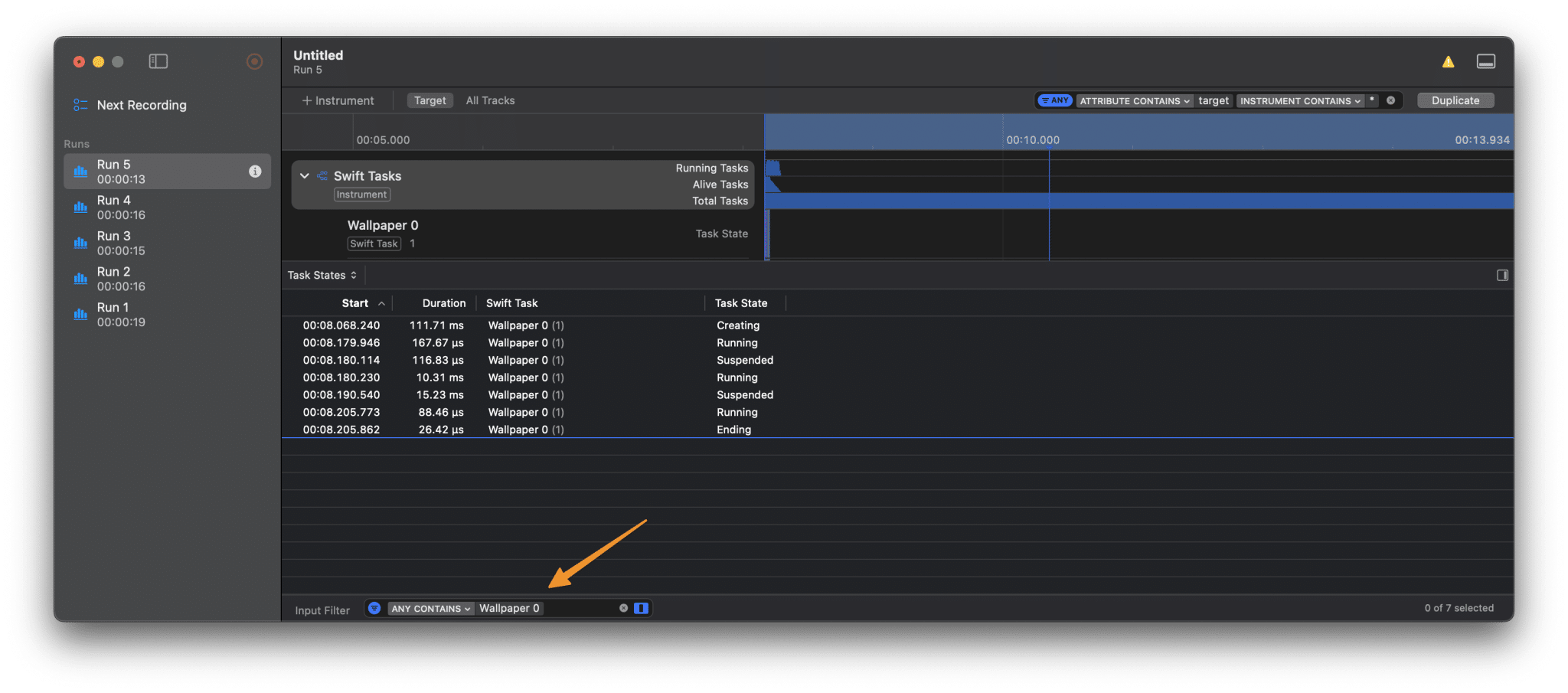

Wallpaper 0 is the first task to run, and we see it suspends twice in total. I’ve created an overview by filtering using the footer:

The question for optimization is whether we can reduce this to a single suspension or no suspension at all. I always love zooming into the specific task, so I indicated Wallpaper 0 in the target overview and zoomed into it accordingly:

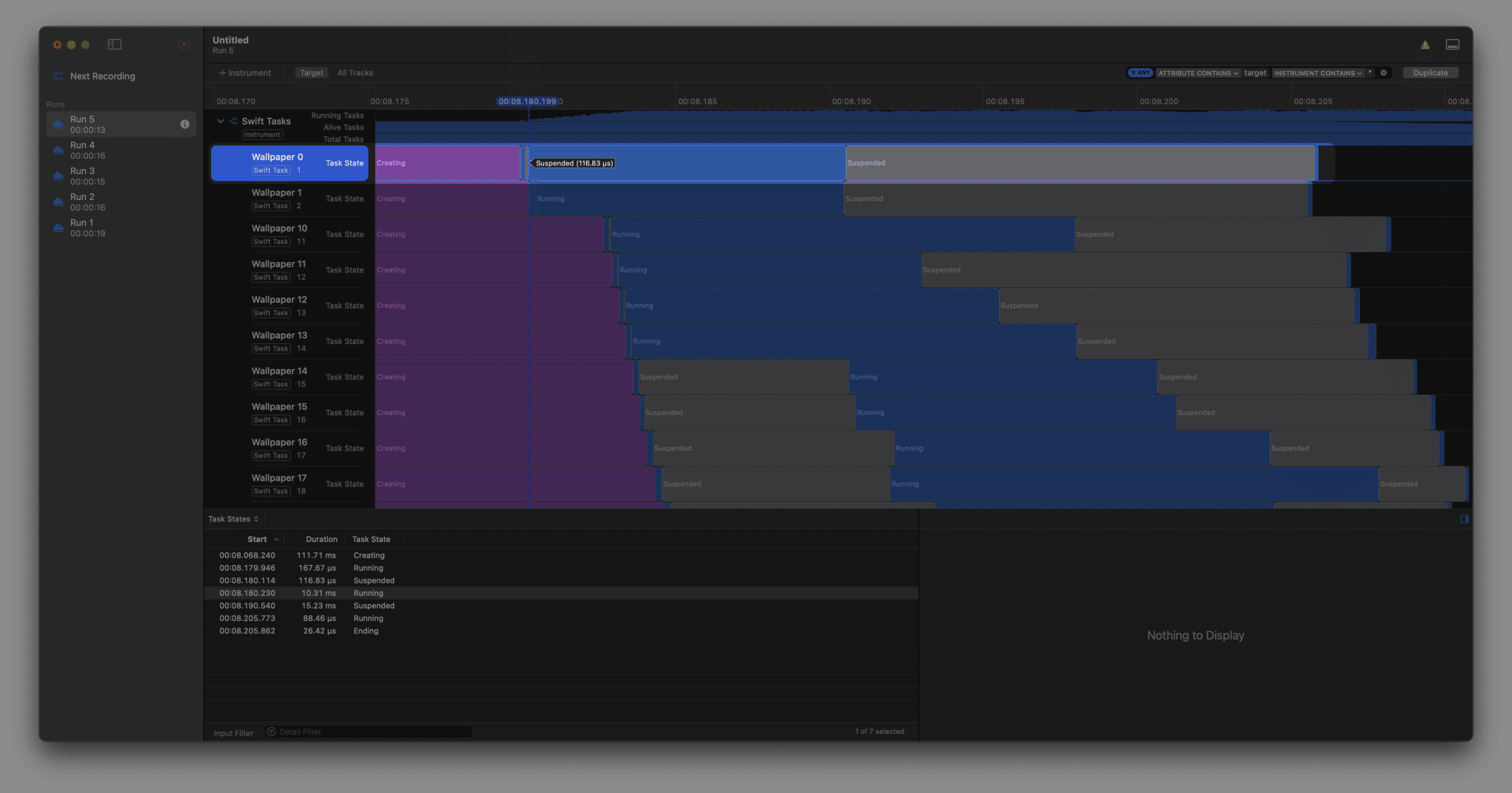

Now, suspending is not necessarily bad. Some methods simply require suspension, and it’s your task to find out. It’s hard to see in the above image, but our Wallpaper 0 task suspends twice. The first suspension is much shorter than the second one:

Navigating to task-related code

With these insights in mind, it’s time to review the related code. You can find a task’s related code by following these steps:

- Click on the

Runningtask state (any state should work) - Open the

Extended Detailwindow - Click on the method that relates to the task

- Use

Open in Source Viewerto navigate to the code

You can replace step 4 by searching for the method in Xcode if you will.

In our case, we know it’s version 4 of our wallpaper generation code:

func regenerateWallpapers_v4() {

wallpapers.removeAll()

isGenerating = true

for index in 0..<numberOfWallpapersToGenerate {

Task(name: "Wallpaper \(index)") {

let wallpaper = await ConcurrentWallpaperGenerator.generate()

self.wallpapers.insert(wallpaper, at: 0)

if self.wallpapers.count == self.numberOfWallpapersToGenerate {

self.isGenerating = false

}

}

}

}

If we zoom into the task method, I would predict suspension as follows:

Task(name: "Wallpaper \(index)") {

/// Task State 1: Running

/// Task State 2: Suspended to go into `ConcurrentWallpaperGenerator`

/// Task State 3: Running while inside `ConcurrentWallpaperGenerator.generate()`

let wallpaper = await ConcurrentWallpaperGenerator.generate()

/// Task State 4: Suspended to go back into this `@MainActor` isolation domain.

/// Task State 5: Running while inserting the wallpaper into `BadGradientsGeneratorViewModel`

self.wallpapers.insert(wallpaper, at: 0)

if self.wallpapers.count == self.numberOfWallpapersToGenerate {

self.isGenerating = false

}

}

Task State 4 in this case relates to the final Suspended state, which is the longer suspension. This is simply because we’re waiting for the @MainActor to let us in. The @MainActor, however, is likely busy with Wallpaper 50+ to start running.

At this point, I’m asking myself these questions:

- Can I start on an arbitrary isolation domain to prevent the first suspension?

- If so, can I maybe remove the

awaitkeyword in front ofConcurrentWallpaperGenerator.generate()since we’re already on a background isolation domain?

This is mostly interesting as well since Wallpaper 99 shows a different state sequence:

By the time Wallpaper 99 runs, several earlier wallpapers return on the @MainActor to store the wallpaper result. In other words, we delay wallpaper generation for no good reason! This is a potential improvement.

Optimizing our code for suspension

Let’s optimize our code by removing the initial suspension point. We can do this by marking the Task as @concurrent and making the wallpaper generation method synchronous:

func regenerateWallpapers_v5() {

wallpapers.removeAll()

isGenerating = true

for index in 0..<numberOfWallpapersToGenerate {

Task(name: "Wallpaper \(index)") { @concurrent in

let wallpaper = SynchronousWallpaperGenerator.generate()

await MainActor.run {

self.wallpapers.insert(wallpaper, at: 0)

if self.wallpapers.count == self.numberOfWallpapersToGenerate {

self.isGenerating = false

}

}

}

}

}

We can use a synchronous wallpaper generator since we know we’re calling it from an asynchronous context. This removes an unnecessary await, improving our performance. We do have to hop back into the @MainActor isolation domain in the end to ensure our wallpapers get added properly.

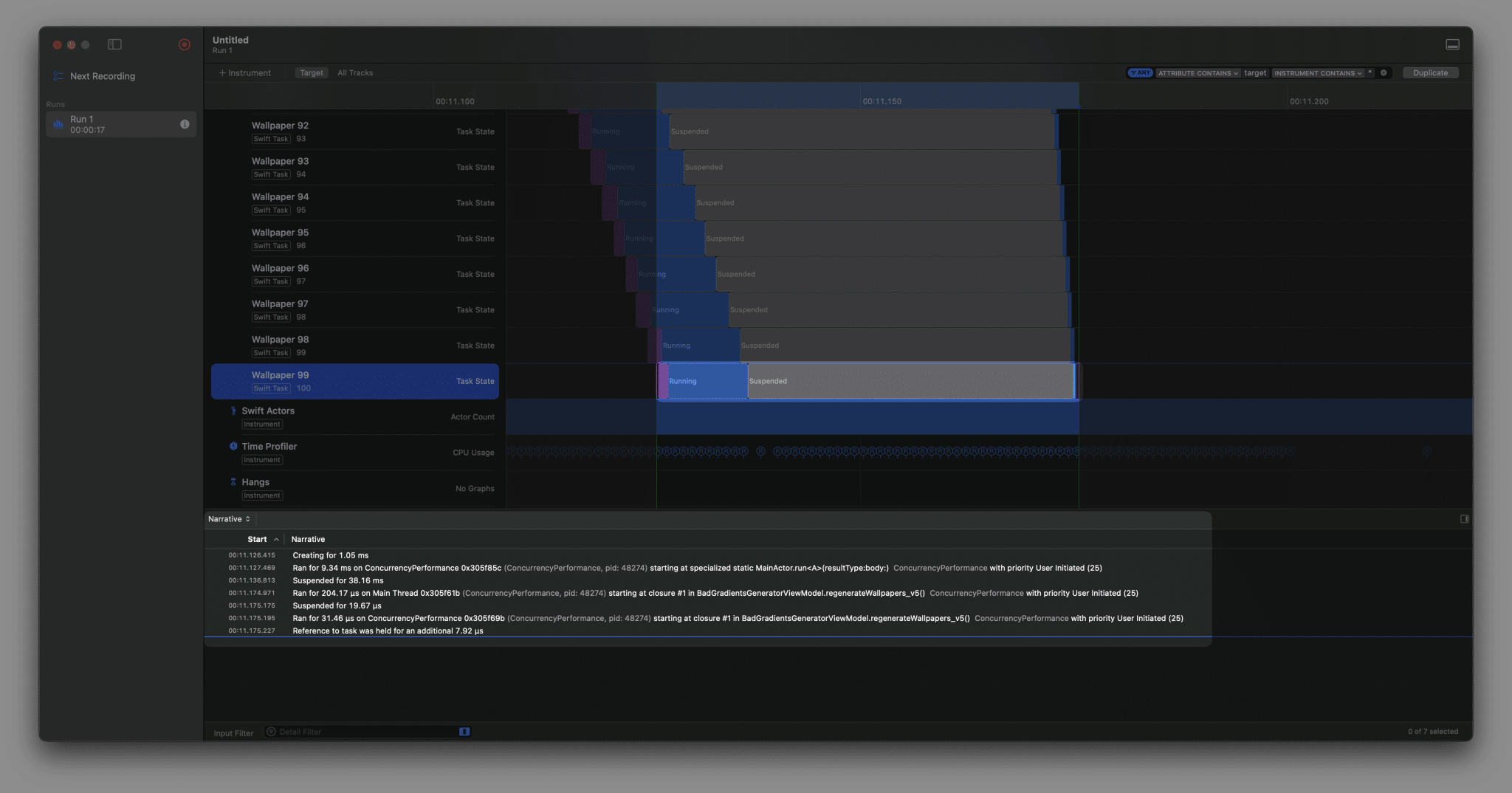

If we go back into instruments, it’s interesting to see the new task states:

I’m purposely looking at the final wallpaper generation since it would be the clearest indication of wallpaper generation starting immediately. As you can see, we’re no longer suspending in the beginning and we’re directly starting the wallpaper generation. The narritive at the bottom shows an explanation of what happened. We’re still suspending in the end to get back from the MainActor.run into our @concurrent context, but this is not hurting any performance of other tasks running at the same time.

Where to go next?

Our wallpaper application has been optimized a lot now. We’ve removed an extra suspension point and await usage, resulting in an even better performance for our application. We could consider optimizing this even further by:

- Only loading the wallpapers into the screen that are actually visible. This will reduce how often we need to switch back to the main actor per task. Depending on the device screen size, we could potentially not switch back for all wallpapers after

Wallpaper 10. - Loading all wallpapers into our array at once. Since our performance improved so much, it doesn’t hurt anymore to load instantly instead of one-by-one.

I’m leaving this as an exercise for you to decide on. The key of this lesson is for you to know how to indicate suspension points and how to optimize your code accordingly. It’s a case-by-case scenario whether or not you need another round of decisions. Note that such a decision could be unrelated to suspension points or concurrency. E.g. whether to load all wallpapers or just a few based on scrolling position is more kind of a UX decision.

In the next lesson, we’re going to look how to choose between serialized, asynchronous, and parallel execution.