Not long ago, many projects went all-in on frameworks like RxSwift and Combine. I still remember the moment Combine was introduced, which made me incredibly excited. Now, a few years later, Combine is no longer receiving updates, and the community appears to be shifting away entirely from Functional Reactive Programming frameworks. At least, they’re less popular, and usage becomes less prominent.

Whether you’ll continue to use these frameworks is entirely up to you, but some of the code will likely have to be migrated to Swift Concurrency. This is possible in most cases, but there are scenarios where you might stick with using a framework like Combine. Let’s dive in!

Is there an observation alternative in Swift Concurrency?

I want to start this lesson by looking at an observation alternative in Swift Concurrency. Combine and RxSwift are often used to observe values and update UI automatically. Using property wrappers like @Published in SwiftUI is an example of using Combine under the hood to reactively redraw a SwiftUI view. How would you do this in Swift Concurrency?

At the moment of writing, the closest Swift 6 solution would be proposal SE-475 Transactional Observation of Values. This proposal has been accepted but not yet implemented. It promises a new Observations type that works as follows:

let names = Observations { person.name }

This example creates an asynchronous sequence that yields a value every time the person’s name property is updated:

Task.detached {

for await name in names {

print("Name was updated to: \(name)")

}

}

It even allows observing in multiple places, which is a close requirement for Combine-based logic:

Task.detached {

for await name in names {

print("New name 1: \(name)")

}

}

Task.detached {

for await name in names {

print("New name 2: \(name)")

}

}

In the above example, both detached tasks will get called when the person’s name changes.

This new observation feature allows you to rebuild Combine pipelines using Swift Concurrency. Especially if you start combining these with the Swift Async Algorithms package, you’ll notice you can get closer to a Combine pipeline.

Open-source alternative: AsyncExtensions

I won’t cover this framework in too much detail, but I find it important enough to share. The AsyncExtensions package is open-sourced and provides async/await alternatives to common types you might know from Combine. Examples are AsyncPassthroughSubject and AsyncCurrentValueSubject. Feel free to check them out and consider whether they’re valuable for your transition. However, before you do, consider going through this whole lesson and see if you can solve things without the Combine-mindset by using Swift Concurrency.

Debouncing in Swift Concurrency

Debouncing is a typical example of using a framework like Combine. We’ve briefly discussed this concept in the Tasks module in the example of a search solution. You only want to perform the actual search when a user stops typing for at least 500 milliseconds. A typical implementation in Combine could look as follows:

$searchQuery

.debounce(for: .milliseconds(500), scheduler: DispatchQueue.main)

.sink(receiveValue: { [weak self] query in

guard !query.isEmpty else {

self?.searchResults = Self.articleTitlesDatabase

return

}

/// A simplified static result and search implementation.

self?.searchResults = Self.articleTitlesDatabase

.filter { $0.lowercased().contains(query.lowercased()) }

})

.store(in: &cancellables)

We observe the searchQuery property and respond to any changes made to it. This works by utilizing @Published and ObservableObject. A few key characteristics of this code:

- It should perform whenever

searchQuerychanges - The change should be debounced to ensure we only execute after at least receiving no input for 500 milliseconds

- After a successful debounce, we want the latest value to be used for searching

We can rewrite this in Swift Concurrency by utilizing Task.sleep and referencing the currently running task. The implementation could look as follows:

/// Using manual cancellation management.

func search(_ query: String) {

/// Cancel any previous searches that might be 'sleeping'.

currentSearchTask?.cancel()

currentSearchTask = Task {

do {

/// Debounce for 0.5 seconds to wait for a pause in typing before executing the search.

try await Task.sleep(for: .milliseconds(500))

print("Starting to search!")

guard !query.isEmpty else {

searchResults = Self.articleTitlesDatabase

return

}

/// A simplified static result and search implementation.

searchResults = Self.articleTitlesDatabase

.filter { $0.lowercased().contains(query.lowercased()) }

} catch {

print("Search was cancelled!")

}

}

}

While not required to make this code work, it’s recommended to migrate to @Observable as well. This is another step forward in migrating away from Combine.

Similarily, we go from this view in Combine:

struct Combine_SearchArticleView: View {

@StateObject private var articleSearcher = Combine_ArticleSearcher()

var body: some View {

NavigationStack {

List {

ForEach(articleSearcher.searchResults, id: \.self) { title in

Text(title)

}

}

}

.searchable(text: $articleSearcher.searchQuery)

}

}

To this view when using Swift Concurrency:

struct Concurrency_SearchArticleView: View {

@State private var searchQuery = ""

@State private var articleSearcher = Concurrency_ArticleSearcher()

var body: some View {

NavigationStack {

List {

ForEach(articleSearcher.searchResults, id: \.self) { title in

Text(title)

}

}

}

.searchable(text: $searchQuery)

.onChange(of: searchQuery) { oldValue, newValue in

articleSearcher.search(newValue)

}

}

}

The code changes are pretty straightforward—we only make use of more direct callbacks rather than Combine pipelines (e.g., by making use of onChange(of: )).

Note

We’ve learned in the Running tasks in SwiftUI lesson that we can make use of the task modifier as well for this code example.

But how does this work for other Combine operators?

The above example represents a relative simple migration. Obviously, I can’t provide examples for all Combine scenarios here, so I’d love to guide you in finding solutions accordingly.

The Swift community has not been quiet when it comes down to migrating away from Combine. There are several discussions on the Swift Forums (like this one on throttling or debouncing) that discuss how to migrate accordingly. It depends on how complex your Combine pipelines are, but I like to look at it this way: there are projects that don’t use Combine at all.

This is a bold statement, but it’s based on my past experience. When I joined WeTransfer in 2017, I was a massive fan of Functional Reactive Programming (I even did a conference talk at Do iOS). The first thing I wanted to add to WeTransfer’s codebase? RxSwift. The developers pushed back and told me we would not need it at all.

Now, I don’t want to start a discussion or push you in any direction. However, I do want to make it clear that many code challenges can be solved without the use of Functional Reactive Programming. It’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking in Combine pipeline operations, endlessly looking for a Swift Concurrency AsyncSequence alternative. While this might be possible by utilizing the earlier-mentioned Swift Async Algorithms package, it might not always be the best solution. You’re rewriting your code either way, so why not optimize it accordingly and think out of the box? I’m sure a lot of code will become easier to reason about and easier to adapt for your colleagues.

A threading risk when using sink with actors

The Combine framework allows you to define so-called pipelines. A common example is a publisher for a given notification, followed by a sink to perform work after receiving:

NotificationCenter.default.publisher(for: .someNotification)

.sink { [weak self] _ in

self?.didReceiveSomeNotification()

}.store(in: &cancellables)

In this case, we’re calling into didReceiveSomeNotification, which will do the actual work. This is a great technique to move logic into a reusable method that you can also use for other cases.

When migrating to Swift Concurrency, you’ll start to define isolation domains. You either opt-in to @MainActor default actor isolation or you explicitly mark a type using the @MainActor attribute. Imagine the latter to be true in this example:

@MainActor

final class NotificationObserver {

private var cancellables: [AnyCancellable] = []

init() {

NotificationCenter.default.publisher(for: .someNotification)

.sink { [weak self] _ in

self?.didReceiveSomeNotification()

}.store(in: &cancellables)

}

private func didReceiveSomeNotification() {

/// Perform some work...

}

}

So far, so good.

Now, let’s dive into the NotificationCenter API. I’d like to quote a relevant Swift Foundation proposal that introduces Concurrency-Safe Notifications. These are actually released in Swift 6.2, so I highly recommend reading up on this proposal, regardless. Here’s the quote from the proposal motivation section:

Notifications today rely on an implicit contract that an observer’s code block will run on the same thread as the poster, requiring the client to look up concurrency contracts in documentation, or defensively apply concurrency mechanisms which may or may not lead to issues. Notifications do allow the observer to specify an

OperationQueueto execute on, but this concurrency model does not provide compile-time checking and may not be desirable to clients using Swift Concurrency.

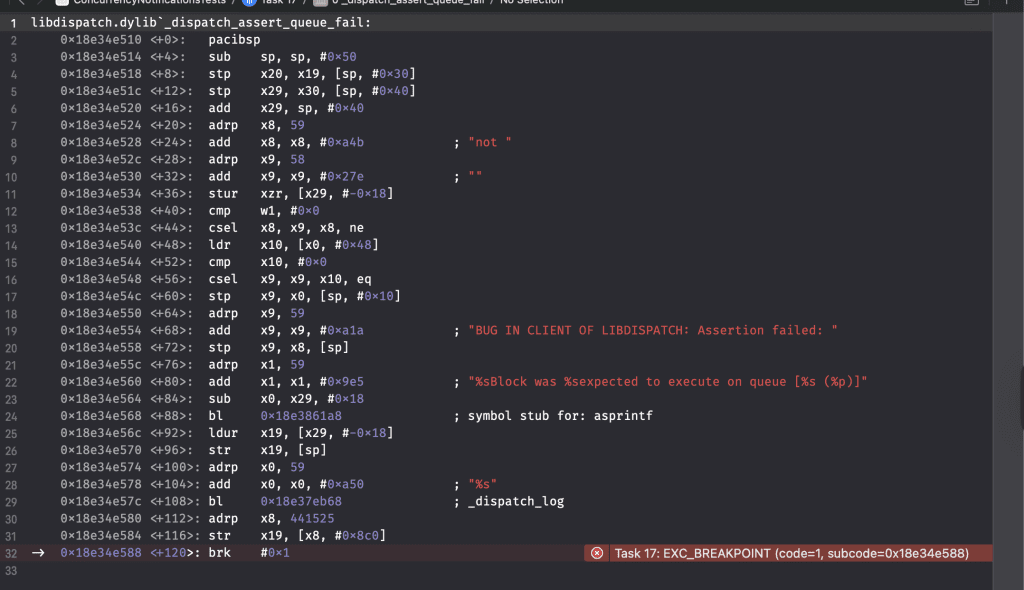

This should ring a lot of bells! And I found out the hard way. After migrating RocketSim to Swift 6.2 and Strict Concurrency, I started testing a final build. Eventually, I ran into the following crash:

A Combine pipeline crash after migrating to Strict Concurrency.

When posting a notification from the main thread, observers on the @MainActor will function as expected. However, as soon as I would post a notification from e.g., a detached task, the above crash would occur. This is simply because NotificationCenter expected the observer to be executed on a specific queue.

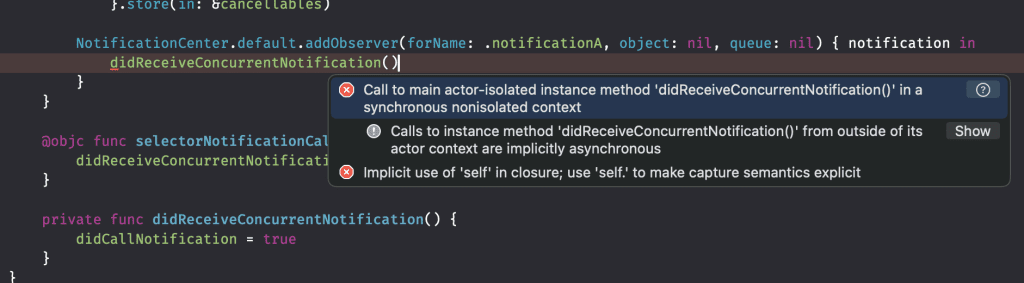

No compile-time feedback for sink closures

A crucial aspect of this crash is that compile-time safety does not apply to sink closures at this point. To illustrate this point, I’d like to show you another way of observing notifications:

A strict concurrency check fails for a non-Combine NotificationCenter observer method.

As you can see, the compiler will tell us right away that what we’re doing is unsafe. The same failure does not arise for our Combine pipeline. In other words, our earlier Combine pipeline to observe a notification and dispatch to a @MainActor isolated method compiles successfully in Swift 6.2 and Xcode 26.

While I’ve opened an issue in the Swift Repository to ask for clarification, there’s a proper way to prevent these crashes in the first place.

Solving Actor isolation issues in Combine

Before explaining the solution, I’d like to once again recommend considering migrating away from Combine pipelines if possible. In this example, we’re observing a notification. It’s perfectly doable to do this in Swift Concurrency as well:

Task { [weak self] in

for await notification in NotificationCenter.default.notifications(named: .someNotification) {

self?.didReceiveSomeNotification()

}

}

You can even observe multiple notifications at once, similar to:

Publishers.Zip3(

NotificationCenter.default.publisher(for: .someNotification),

NotificationCenter.default.publisher(for: .notificationB),

NotificationCenter.default.publisher(for: .notificationC)

).sink { [weak self] _ in

self?.didReceiveSomeNotification()

}.store(in: &cancellables)

By using a custom extension from the Discarding Task Group lesson:

Task { [weak self] in

for await _ in NotificationCenter.default.notifications(named: [.someNotification, .notificationB, .notificationC]) {

self?.didReceiveSomeNotification()

}

}

However, you might not want to migrate all your Combine pipelines immediately. Therefore, it’s good to know that there’s another solution.

The earlier defined NotificationObserver Combine pipeline looked fine, but it does not configure any preferred thread to receive messages on. You might think using receive(on: ) will be enough to solve this issue, but it’s not. Methods like:

NotificationCenter.default.addObserver(self, selector: #selector(selectorNotificationCalled), name: .someNotification, object: nil)

And:

NotificationCenter.default.publisher(for: .someNotification)

Register the thread when being called. If you call the above methods on the main thread, notifications posted from another thread in Swift Concurrency will result in the earlier shown crash. This is simply reproducible by using the following code to post a notification:

struct DetachedNotificationPoster {

func post() async {

await Task.detached {

NotificationCenter.default.post(name: .someNotification, object: nil)

}.value

}

}

For Combine pipelines observing notifications, I only see rewriting to the Swift Concurrency as a solution. For other pipelines, you can either use the receive(on: ) modifier to ensure you’re receiving callbacks on a matching thread, but it will only work for @MainActor isolation in combination with DispatchQueue.main. Instead, you can make use of a Task inside the sink modifier:

somePublisher

.sink { [weak self] _ in

Task {

/// Do some work...

}

}.store(in: &cancellables)

However, once again, I decided to rewrite away from Combine as much as possible and benefit from compile-time thread safety. It requires a mindset shift, and it may be quite some work for larger projects, but if you have the capacity, you’ll end up with a future-proof project that benefits from compile-time thread-safety checks.

Summary

Migrating Combine or RxSwift pipelines to Swift Concurrency can be challenging at first, but doable in the end. Especially if you let go of the Combine mindset, you’ll find yourself writing strict concurrency code solutions that are easier to reason about without the requirement of Functional Reactive Programming knowledge. In cases where you really want to benefit from operators like removeDuplicates or zip, you can check out the open-source package by Apple: Swift Async Algorithms.

In the next lesson, we’re going to look into thread-safe notifications.