While the previous lesson gave a brief introduction to memory management with tasks, there’s more to learn when diving into the details. The goal of this lesson is for you to understand when retain cycles happen and when they can cause unexpected trouble.

But before we dive into concurrency-related memory management, I first want to explain the basics for those that are unfamiliar with memory management in the first place.

What is a retain cycle?

A retain cycle happens when two (or more) objects hold strong references to each other, preventing either from being deallocated because each keeps the other alive.

In Swift, objects are automatically kept alive as long as something holds a strong reference to them. Normally, when no more references exist, the object is freed from memory. But if two objects reference each other strongly, they’re stuck in memory—even if nothing else uses them.

Here’s a simple example:

class A {

var b: B?

}

class B {

var a: A?

}

let a = A()

let b = B()

/// Connect both instances:

a.b = b

b.a = a

In this code:

- a holds a strong reference to b

- b holds a strong reference to a

Even if a and b go out of scope, they won’t be deallocated because they keep each other alive.

Why retain cycles matter with Tasks

A similar situation can happen when a Task captures self strongly. If self owns the task (directly or indirectly), and the task holds on to self, they keep each other alive—creating a retain cycle.

This can easily happen when you’re building some kind of polling mechanism. Imagine the following image loader:

@MainActor

final class ImageLoader {

var task: Task<Void, Never>?

init() {

print("Init!")

}

deinit {

print("Deinit!")

}

func startPollingWithRetainCycle() {

task = Task {

while true {

self.pollNewImages()

try? await Task.sleep(for: .seconds(1))

}

}

}

private func pollNewImages() {

print("Polling for new images...")

}

}

The image loader polls for new images every single second. Since we’re using a consistent while loop, we’ll never have the option to break out. You might expect this loop to stop running once ImageLoader gets deallocated, but the opposite is true.

If we would call it as follows:

var loader: ImageLoader? = .init()

loader?.startPollingWithRetainCycle()

loader = nil

print("Set loader to nil")

The print statements would be:

/// Prints:

/// Init!

/// Set loader to nil

/// Polling for new images...

/// Polling for new images...

/// Polling for new images...

/// ...

/// (DEINIT never printed because of retain cycle)

Instead, we can rewrite the code to work without a retain cycle:

func startPollingWithoutRetainCycle() {

task = Task { [weak self] in

while let self = self {

self.pollNewImages()

try? await Task.sleep(for: .seconds(1))

}

}

}

Running this code example would result in the following print statements:

/// Prints:

/// Init!

/// Deinit!

/// Set loader to nil

This example demonstrates why it’s important to keep an eye sharp on your strong references. When working with asynchronous sequences or long-running tasks, it’s easy to run into retain cycles.

One-way retention example

While retain cycles are all about two or more objects that retain each other, you can also experience what I like to call a one-way retention. The previous lesson actually demonstrated one: a task retains self while self does not retain the task.

The result is a task that completes executing and self which gets released only after the task completes.

Simply said, the task releases its strong reference to self after completion, as it no longer needs it. This is an essential difference from the above long-running code example, in which the task never completes.

To remind you, here are the print statements from the previous lesson code example:

/// Prints:

/// Perform network request

/// Set viewModel to nil

/// Finished network request

/// DEINIT!

As you can see, the deinit gets called after the network request is completed.

Manually breaking a retain cycle

There could be cases where you can’t avoid having a strong reference to self. Imagine the following common example where we’re monitoring a notification using an asynchronous sequence:

@MainActor

@Observable

final class AppLifecycleViewModel {

private(set) var isActive: Bool = false

private var task: Task<Void, Never>?

deinit {

print("Deinit!")

}

func startObservingDidBecomeActive() {

let center = NotificationCenter.default

task = Task {

for await _ in center.notifications(named: Application.didBecomeActiveNotification) {

isActive = true

print("App became active")

}

}

}

func stopObservingDidBecomeActive() {

task?.cancel()

}

}

Note

Just so you know, this is not a complete example as we’re not setting isActive to false anywhere, but it shows the case I want to make.

If we would call this code as follows:

var viewModel: AppLifecycleViewModel? = .init()

viewModel?.startObservingDidBecomeActive()

viewModel = nil

print("Set viewModel to nil")

We would get the following print statements:

/// Prints:

/// Set viewModel to nil

/// App became active

/// App became active

/// ...

This is happening because we’re still monitoring for incoming notifications and keeping a strong reference to self via the isActive property.

The correct way of solving this would be to stop observing before releasing:

var viewModel: AppLifecycleViewModel? = .init()

viewModel?.startObservingDidBecomeActive()

viewModel?.stopObservingDidBecomeActive()

viewModel = nil

print("Set viewModel to nil")

/// Prints:

/// Set viewModel to nil

/// Deinit!

But can’t I use the deinit to stop observing?

Well, ideally, you would!

However, since the view model never gets released, it will also never call into the deinit method. Therefore, you’re required to take ownership of this yourself and make sure to stop observing at appropriate times.

Talking about deinit, I can’t use it for clean up when I’m actor isolated?

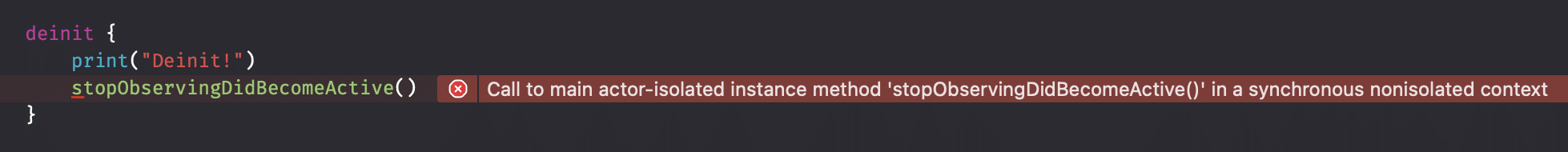

You’re right, you’re likely running into an error like:

Which would look as follows in the context of the above code example:

Starting from Swift 6.2, you’ll be able to define the deinit method as isolated too:

isolated deinit {

print("Deinit!")

stopObservingDidBecomeActive()

}

However, once again, this won’t be enough to break retain cycles as they’ll prevent the deinit from getting called at all.

Summary

In this lesson we’ve seen more in-depth examples of common retain cycles that can happen in any of your projects. Whenever you make use of asynchronous sequences or long running tasks, it’s easy to run into any form of retain cycle. Luckily enough, there are several ways to prevent or break them accordingly.

Up next is an assessment to validate your learnings, good luck!