Have you ever found yourself trying to call an actor-isolated method from within a deinit? I certainly did, and I concluded that I had to find another way to tear down. That changes with the introduction of isolated deinit in Swift 6.2 (SE-371).

Understanding isolated deinit

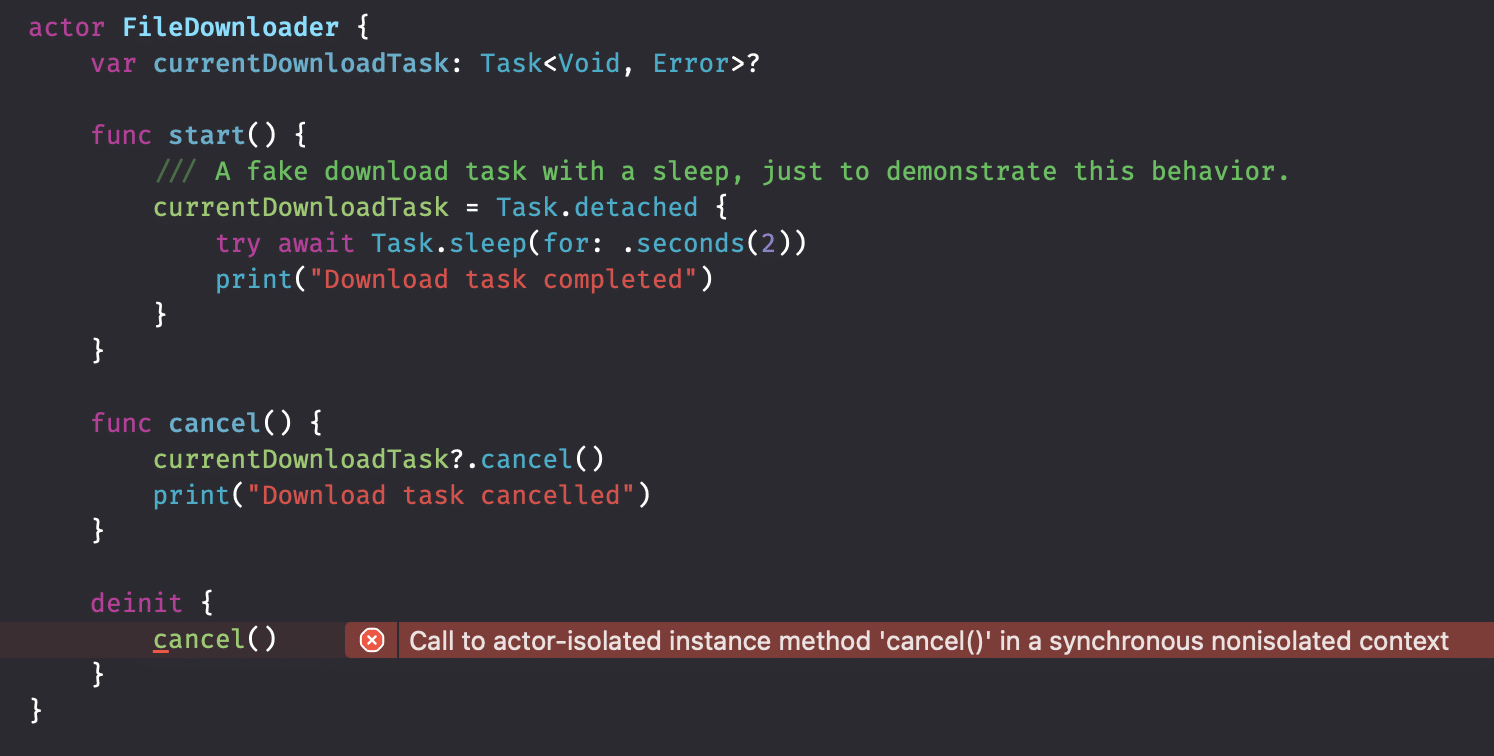

Let’s start by introducing a common example. In this case, I created a FileDownloader actor that looks as follows:

actor FileDownloader {

var currentDownloadTask: Task<Void, Error>?

func start() {

/// A fake download task with a sleep, just to demonstrate this behavior.

currentDownloadTask = Task.detached {

try await Task.sleep(for: .seconds(2))

print("Download task completed")

}

}

func cancel() {

currentDownloadTask?.cancel()

print("Download task cancelled")

}

}

For the sake of this example, it’s just mimicking download behavior by using a Task.sleep.

What’s common in these types is to cancel the running download task from inside the deinit:

However, as you can see, it results in an actor-isolated compiler issue. This is caused by the fact that the deinit method is nonisolated by default. The compiler issue also mentions it’s synchronous, as it will always execute synchronously. This is simply because it’s executed at the moment the object is being released. An asynchronous deinit would extend the lifetime of a type, making it unpredictable when it’s really released (do we need a deinit-deinit? ;-)).

With the introduction of isolated synchronous deinit, we can now solve the above compiler issue by using isolated deinit:

isolated deinit {

cancel()

}

This indicates that the execution of the deinit body should be scheduled on the actor’s executor. This allows us to call into the actor-isolated cancel method and clean up state accordingly.

Minimum required OS version

It took a considerable amount of time for this proposal to be implemented in Swift. The first review happened in 2022, while Swift 6.2 got released in 2025 (!!). It was even scheduled for Swift 6.1, but was found too risky just before the release. Either way, it’s finally here, but not without limitations.

Implementing this feature has been a challenge. It kind of makes sense: the deinit happens at the moment an object is being released. Extending this lifetime would be troublesome and introduce all kinds of new implications. That’s also why you’ll find out that this feature is only available for iOS 18.4+ and macOS 15.4+.

Summary

Using isolated deinit will be a great escape route in cases you want to clean up state when an object gets released. Without it, you would need to explicitly call methods like cancel() before the object gets released. This is tricky, as it’s not always clear where objects will be released. Unfortunately, there’s a minimum OS requirement, so we might have to wait a little bit before we can start using this throughout existing projects.

In the next lesson, we’re going to add isolated conformance to protocols.