While actors are effective in most cases, there are situations where you may want to avoid introducing concurrency right away. The overhead of async/await isn’t always necessary, especially if you only need to protect a single mutable piece of data.

Note that this is a case-by-case scenario—most of the time, you’ll be fine using an actor. I’ve used a mutex when I wanted to keep my code non-isolated, making it accessible from any isolation domain without adding extra suspension points or asynchronous contexts. WWDC introduced a new Synchronization framework, along with a standardized Mutex that works well with Swift Concurrency. In this lesson, we’ll explore this Mutex in more detail.

Note

The relevant Swift Evolution proposal for Swift’s Mutex can be found here: SE-433 Synchronous Mutual Exclusion Lock.

What is a Swift Lock?

Before diving into Swift’s Mutex, I want you to understand its family: locks.

A Swift Lock, or locks in general, allow you to ensure only one thread or task can access a piece of data at a time. It ensures thread-safety access and prevents exceptions caused by data being accessed simultaneously. The latter is called a data race, and it’s a common cause of crashes in applications. A data race happens when two or more threads access the same memory location at the same time, at least one write occurs, and there’s no proper synchronization to control the access.

What is the difference between a Mutex and a Lock?

All mutexes are locks, but not all locks are mutexes. Mutex is a shorthand for mutual exclusion, and it’s a specific type of lock that strictly enforces mutual exclusion, meaning only one thread can own it at a time. This ownership means it can only be unlocked by the same thread or task that locked it.

This strict ownership model makes mutexes reliable and helps prevent specific bugs related to incorrect unlocking. On the other hand, the term “lock” is broader and can refer to different synchronization tools, like reentrant locks, reader-writer locks, or unfair locks. While both ensure exclusive access to shared resources, mutexes focus on simplicity and strict ownership, whereas locks offer more flexibility and can be tailored to different concurrency scenarios.

Using Swift’s Mutex lock from the Synchronization framework

Now that we know the difference between a lock and a mutex, it’s time to dive into Apple’s Synchronization framework. This framework was announced during WWDC 24 and is available from iOS 18 and macOS 15. This is important for apps that still have to support older OS versions.

In this example, we’re going to use a Mutex Swift lock to protect a counter. This is a classic example to demonstrate the concept of a Mutex:

final class Counter {

/// Use the Mutex to protect the count value.

private let count = Mutex<Int>(0)

/// Provide a public accessor to read the current count value.

var currentCount: Int {

count.withLock { currentCount in

return currentCount

}

}

func increment() {

count.withLock { currentCount in

currentCount += 1

}

}

func decrement() {

count.withLock { currentCount in

currentCount -= 1

}

}

}

As you can see, we’ve used the Mutex to protect the stored count value. Doing so offers a thread-safe way to keep track of a count. We’ve created public accessors to communicate with the count and the Mutex enforces us to make use of the withLock method.

This method provides an inout access to the count property. This basically means that we can directly interact with the mutable value of count. Therefore, we can update the count using:

currentCount += 1

The withLock method forwards any returned values. This is why we can return the current count by simply returning the closure parameter:

var currentCount: Int {

count.withLock { currentCount in

return currentCount

}

}

Throwing errors from within a Mutex

It’s also possible to throw an error from within the withLock closure. For example, we could decide to throw a reachedZero error when someone tries to decrement below zero:

func decrement() throws {

try count.withLock { currentCount in

guard currentCount > 0 else {

throw Error.reachedZero

}

currentCount -= 1

}

}

A lock that works great with Swift Concurrency

The Mutex is a Swift lock that works great with Swift Concurrency. It’s unconditionally Sendable, which means that it provides thread-safe (Sendable) access to any non-Sendable value.

Recently, I was working with NSBezierPath, which is a mutable non-Sendable type. I used this path to store touches for Simulator recordings in RocketSim. I was able to work safely with this instance by wrapping it inside a Mutex:

final class TouchesCapturer: Sendable {

let path = Mutex<NSBezierPath>(NSBezierPath())

func storeTouch(_ point: NSPoint) {

path.withLock { path in

path.move(to: point)

}

}

}

This made my TouchesCapturer conform to Sendable and demonstrates how you can write a solution to work with non-Sendable types.

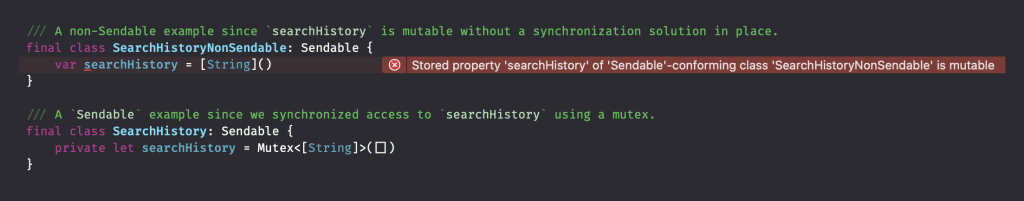

We can demonstrate this same concept by looking at a search history example in which we store search queries inside a mutable array:

Using a Swift lock like a mutex can help you create sendable access to data.

Shouldn’t I use an actor instead of locks in Swift Concurrency?

I bet many of you are wondering why Apple introduced this Mutex while it’s also working on modern concurrency APIs. Shouldn’t you use an actor in these cases?

Actors are indeed a fantastic tool for protecting mutable state in many scenarios, but they aren’t always the right fit. There are situations where you need synchronous, immediate access to data without introducing the async keyword or suspension points. Sometimes, your code needs to interact with APIs or legacy code that doesn’t support Swift Concurrency at all, making actors impractical or impossible to adopt.

Moreover, actors come with certain design trade-offs — they isolate state and enforce exclusive access through asynchronous messages, which is great for safety but can introduce additional overhead and complexity when low-level, fine-grained locking is required. In these cases, a Mutex offers a lightweight and familiar synchronization primitive that can be used without changing your code to be asynchronous or refactoring everything around await.

Mutexs are thread-blocking

It’s important to note that a mutex provides non-recursive exclusive access to the state it protects by blocking threads attempting to acquire the lock. This results in only one execution context accessing the value at a time, allowing exclusive access. In many cases, this is perfectly fine, especially when contention is low and the work done while holding the lock is short-lived.

Summary

Ultimately, it’s not about choosing one over the other universally — it’s about picking the right tool for the job. Actors shine when you can adopt an async model and benefit from clear logical isolation, whereas mutexes fill the gaps where synchronous, immediate access, and minimal disruption are necessary. You now have an extra tool at hand!