Throughout the lessons so far, you’ve seen several actors in action. It’s the classic chicken-egg story: I had to mention them before even though I didn’t explain them in depth yet!

This module will be all about actors, global actors, isolated and nonisolated access. It’s an exciting module which will also guide you through using @MainActor when working with UI changes. Before we dive into the details for each, I first want you to better understand the concept of actors.

What is an actor?

In Swift Concurrency, an actor is a type that protects its own data. You can think of it as a class, but one that’s wrapped in a safety bubble — it guarantees that only one task can access its mutable state at a time.

Here’s a simple actor example that you might recognize from previous lessons:

actor Counter {

var value = 0

func increment() {

value += 1

}

}

It looks a lot like a regular class, but under the hood, Swift makes sure that increment() is never called simultaneously by multiple tasks. This means you can safely use this counter across threads without worrying about data races. Just like classes, actors are reference types.

Actors are the foundation for safe concurrency in Swift. You’ll see them used a lot — especially when working with shared mutable state or when updating UI through the global @MainActor.

How actor isolation works

The core of an actor is a powerful promise:

“Only one task at a time can access my mutable state.”

This is what we call actor isolation and it’s what makes actors safe to use in a concurrent context.

Let’s look at an example:

actor BankAccount {

var balance: Int = 0

func deposit(_ amount: Int) {

balance += amount

}

func getBalance() -> Int {

return balance

}

}

The balance property is isolated to the BankAccount actor. That means you can’t access balance directly from outside the actor. You’re forced to go through one of the actor’s methods which Swift ensures are run one at a time.

I hear you thinking:

“But

balanceis a non-private property, so I can mutate outside of the actor as well, right?”

Well, that’s not the case! Imagine the following piece of code:

let actor = BankAccount()

actor.balance += 1

This would result in the following compiler error:

In other words, you’re forced to use one of the actor’s methods for mutations:

let actor = BankAccount()

await actor.deposit(1)

This demonstrates how actor isolation works. Swift makes sure only one task is accessing deposit() at that moment. If another task tries to call deposit() or getBalance() at the same time, it will await its turn.

And that summarizes actor isolation: it serializes access to state. You don’t need to think about locks, queues, or any of the other low-level locking mechanisms—Swift Concurrency handles it all for you.

How is actor isolation enforced?

Under the hood, each actor has its own executor — kind of like its own private queue. Tasks sent to the actor get run on that executor, one after the other. This ensures that your state stays consistent, even when accessed from multiple tasks or threads.

What is an actor executor?

Every actor in Swift has something what we call an executor. You can think of it as a serial dispatch queue that manages who gets access to the actor’s isolation domain.

Each task accessing an actor will run on that actor’s executor, ensuring safe, exclusive access to the actor’s internals. While it’s possible to change an actor’s executor, you generally don’t have to. It uses a default executor under the hood which makes all access run via the cooperative thread pool that we discussed in the introduction of this course. That means it doesn’t block threads unnecessarily, and Swift Concurrency can move work around efficiently behind the scenes.

Why do we need actors?

Hopefully, this answer is redundant for you as we’ve already discussed thread-safety, data races, and race conditions in the previous module. Actors synchronize access to shared mutable state and makes sure there’s only one thread accessing mutable state at the same time.

Accessing actor properties and methods

Since an actor manages who can access shared state, it could be that you’ll have to await access. Therefore, you’ll always have to use await when accessing properties or methods from an actor.

We’ve learned that it’s impossible to mutate properties directly, but we can read properties inline:

let actor = BankAccount()

await actor.deposit(1)

print(await actor.balance)

Yet, you’ll have to use await since the actor might just have given access to another task to send a deposit to the bank account. The above code example also shows how we call into the deposit(...) method using await.

Altogether, you can see an actor as a traffic light. You might be driving into the actor right away since the light is green and no others are inside the actor yet. However, you don’t know beforehand, so an await ensures we’re prepared for any case.

Actors are reference types but still different compared to classes

Actors are reference types which in short means that copies refer to the same piece of data. Therefore, modifying the copy will also modify the original instance as they point to the same shared instance.

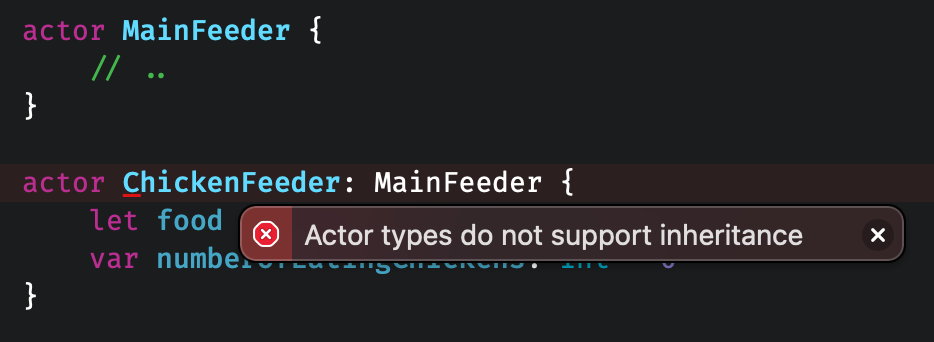

Yet, Actors have an important difference compared to classes: they do not support inheritance.

Actors in Swift are almost like classes, but don’t support inheritance.

Not supporting inheritance means there’s no need for features like the convenience and required initializers, overriding, class members, or open and final statements.

However, the biggest difference is defined by the main responsibility of actors, which is isolating access to data.

Actors can inherit from NSObject (only for Objective-C interoperability)

There’s one exception when it comes down to inheritance: NSObject. This is to support Objective-C interoperability. For example:

actor Example: NSObject {

// valid for Objective-C use (e.g. with delegates, selectors)

}

Summary

There are much more details to cover regarding actors, but this brief introduction should set you up for better understanding the more in-depth lessons that will follow. Each actor has its own executor, ensuring shared state access is serialized and isolated. You can only modify properties via an actor’s method, but you can read properties directly. All access needs to be done using await since you’ll never know whether somebody is accessing the actor already.

In the next lesson, you’ll be introduced to Global Actors.